The Subject in Subjective Time: A New Approach to Aggregating Wellbeing

Discuss this article on the EA Forum here.

What follows is a lightly edited version of the thesis I wrote for my Bioethics MA program. I’m hoping to do more with this in the future, including seeking publication and/or expanding it into a dissertation or short book. In its current state, I feel like it is in pretty rough shape. I hope it is useful and interesting for people as puzzled by this very niche philosophical worry as me, but I’m also looking for feedback on how I can improve it. There’s no guarantee I will take it, or even do anything further with this piece, but I would still appreciate the feedback. I may or may not interact much in the comments section.

I. Introduction

Duration is an essential component of many theories of wellbeing. While there are theories of wellbeing that are sufficiently discretized that time isn’t so obviously relevant to them, like achievements, it is hard to deny that time matters to some parts of a moral patient’s wellbeing. A five-minute headache is better than an hour-long headache, all else held equal. A love that lasts for decades provides more meaning to a life than one that last years or months, all else held equal. The fulfillment of a desire you have had for years matters more than the fulfillment of a desire you have merely had for minutes, all else held equal. However, in our day to day lives we encounter time in two ways, objectively and subjectively. What do we do when the two disagree?

This problem reached my attention years ago when I was reflecting on the relationship between my own theoretical leaning, utilitarianism, and the idea of aggregating interests. Aggregation between lives is known for its counterintuitive implications and the rich discourse around this, but I am uncomfortable with aggregation within lives as well. Some of this is because I feel the problems of interpersonal aggregation remain in the intrapersonal case, but there was also a problem I hadn’t seen any academic discussion of at the time – objective time seemed to map the objective span of wellbeing if you plot each moment of wellbeing out to aggregate, but it is subjective time we actually care about.

Aggregation of these objective moments gives a good explanation of our normal intuitions about time and wellbeing, but it fails to explain our intuitions about time whenever these senses of it come apart. As I will attempt to motivate later, the intuition that it is subjective time that matters is very strong in cases where the two substantially differ. Indeed, although the distinction rarely appears in papers at all, the main way I have seen it brought up (for instance in “The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence 1” by Nick Bostrom and Eliezer Yudkowsky) is merely to notice there is a difference, and to effectively just state that it is subjective time, of course, that we should care about.

I have very rarely run into a treatment dedicated to the “why”, the closest I have seen is the writing of Jason Schukraft 2, with his justification for why it is subjective time that matters for Rethink Priorities’ “Moral Weights” project. His justification is similar to an answer I have heard in some form several times from defenders: We measure other values of consciousness subjectively, such as happiness and suffering, why shouldn’t we measure time subjectively as well? I believe without more elaboration, this explanation has the downside that it both gives no attention to the idea that time matters because it tells us “how much” of an experience there actually is, and has the downside that it seems irrelevant to any theory of wellbeing other than hedonism.

It also, crucially, fails to engage with the question of what exactly subjective time even is. This latter issue is the basis for perhaps the most substantial writing on the relevance of subjective versus objective time I have found so far, Andreas Mogensen’s recent preprint “Welfare and Felt Duration” 3. This paper ably goes through many of the problems with the case for subjective time. In the rest of this paper, I hope to give as dedicated a treatment to the case for caring about subjective time for wellbeing. This is both to draw out a theory that most people in this conversation want to believe, but have so far not developed to my satisfaction, and to defend against Mogensen’s better drawn out case in the other direction.

In section II, I will start by arguing that “subjective time”, as distinguished from “objective time”, does exist. I will do this primarily by applying modest functionalist claims to thought experiments in which all the functions in minds are slowed down or sped up. In section III I will defend the idea of objective time, against the claim that Einsteinian Relativity undermines it. In section IV I will use thought experiments in which we find ourselves living subjectively altered lives, to pump the intuition that subjective time determines wellbeing in such cases. I will also argue, however, that it is hard to distinguish this intuition from delusions if we look for the source of value at each moment in turn. In section V I introduce Mogensen’s paper, which considers bigger picture theories of what subjective time actually is, and argue for the cognitive account of subjective time, over the frame-rate account. In section VI I examine why I think we should be skeptical of Mogensen’s argument that speed of cognition isn’t a good basis for measuring wellbeing.

In section VII I distinguish two different types of theory of wellbeing, one which takes wellbeing as simply some amount of impersonal value in the universe, and the other of which takes wellbeing as valuable only insofar as it is valuable to moral subjects like people. I develop this into an account in which changing the subjective time changes the amount of wellbeing happening to a given amount of subject. In section VIII I consider Mogensen’s response that we are our feelings, so they are both the subject and the subject’s wellbeing, and I begin to raise complications that result from this view. Finally, in section IX, I consider why illusionism and some continental philosophy about subjective time present a good example of how subjective time could be what matters, even if we view the subjects as the same thing as their conscious experiences.

II. Subjective Time is Real:

To start with, there are fairly easy ways to spell out the relevance of “objective time” of the sort used in physics to describe the behavior and interactions of systems in the third person. If you look at a given amount of wellbeing someone experiences at a given time, and assign a value to it, there are more of these moments of time in longer periods of experience than shorter ones, and so more aggregate wellbeing. In short, an hour headache matters more than a five minute headache because there is more of it. The longer love provides more meaning because each moment of it was meaningful and it has more such moments, the longer held desire matters more because fulfilling it satisfies more desires.

The trouble is, there is another possible sort of time, time as we experience it in the first person, subjective time. At first blush this does not seem like a sensible difference to draw, like asking whether the word “tall” is taller or shorter than a skyscraper. What is a subjective second? Whatever an objective second feels like inside a mind stretched out over it (a point Mogensen raises as well 4). The trouble isn’t with matching any given experience of time to the objective time it spans at all, it is doing so uniquely. We can imagine experiencing time in a way that normally corresponds to how we experience one second, but it could be that the experience plays out over the course of one hour, or vice versa. If a second could only feel one way from the inside, then it wouldn’t even make conceptual sense to talk about a mismatch between subjective and objective time, but we might make different tradeoffs if we are primarily paying attention to subjective time for wellbeing if you can change subjective time while holding objective time constant.

The changeability of subjective time is not immediately obvious or completely uncontroversial – humans rarely have reliable reports of different subjective experiences of time. The cases where reports like this tend to be most common are things like drug use, dreams, and near-death experiences, none of which involve a particularly reliable narrator. The most dramatic cases we are likely to encounter in the present-day real world are non-human animals. Not only can we not communicate with them, but so much of their experience differs from humans, that we need a clear idea of what part of the mind corresponds to subjective experience of time. There doesn’t seem to be great consensus on this, since we don’t get reliable reports from humans in the way we do when locating things like the neural basis for hearing or vision. The next minds of this sort we are likely to encounter are the first conscious AI systems which, unless things change soon, are likely to have even more inscrutable minds with no obvious structures in common with humans.

The philosopher, however, rarely sees current possibility or likelihood as a principled barrier to distinguishing concepts. It is possible that at some point in the future we will be able to digitally simulate all the operations of the human brain on a sufficiently advanced computer. If this is possible, then we can imagine executing experiences as computer functions, and so trivially run them faster or slower. If such a system is conscious, it then requires very modest functionalist claims to say that it is possible to change the objective time that passes that it takes to go through subjectively identical experiences. Namely, if there is apparent interaction between the mind and the environment the mind is in, this is mediated functionally. Environmental stimulus produces functional reactions in the brain that correspond to conscious reactions in the mind, and conscious commands to the body produce functional reactions in the brain that cause apparently corresponding actions. This would, for instance, rule out that the mind is viewing actions outside the body as though it is an inert viewer of a movie shot in first person. If brain functions “react” or “act” in certain ways, this corresponds to the same stream of conscious mental action and reaction. I will call this the “modest functionalist claim”.

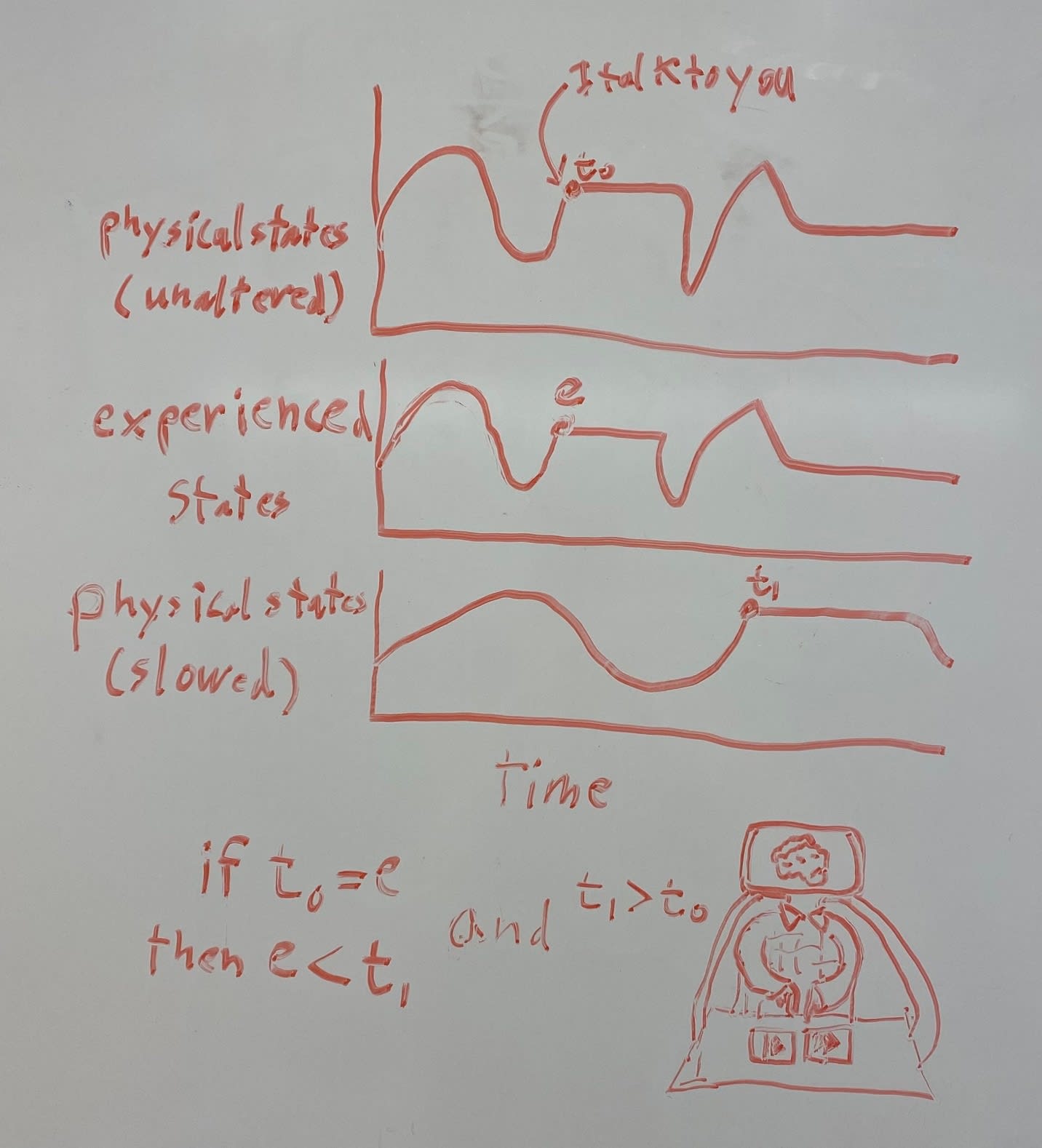

To agree to this modest functionalist claim, and agree aforementioned simulation is conscious, but deny that the subjective time can’t go at a different rate by changing how fast the program is run, leads to absurdity. It seems as though you need to believe that the subjective experience can be in some sense “jet lagged”, such that even as someone talks to you, they aren’t having an experience as of talking to anyone yet, or even more absurd, if the simulation is slowed down, you could only now be talking to someone, while they had the experience as of talking to you in the past.

You can also simply deny that it’s possible to run a conscious simulation at different speeds at all by denying either that such a simulation would be conscious, or that you can change the speed of all relevant functions of it even if you do simulate it successfully. The former could be argued through a sort of substrate dependence. Maybe consciousness requires implementation in a particular material, or at least in some way that is inconsistent with digital computers – just as digital rain is not wet. Fine. I think this is unlikely, and think for instance David Chalmers’ fading and dancing qualia arguments 5 are more persuasive on this point than the counter arguments, but I also think it is reasonable to just be unsure on this question.

Imagine slowing down all the processes of the mind in our normal bodies then. Philosophers aren’t restricted to science fiction, imagine a warlock casting a slow-motion spell on you if you’d like. Regardless of what it is in the mind that corresponds to subjective time experience, it will be slowed with the rest, the proof of concept remains. The most obvious rejoinder to this is to say there are no warlocks in the real world! In the real world, we can’t fully slow motion or fast motion a mind, there is some crucial process that can’t be changed in this way at all. This is the second, and I think ultimately most relevant worry – that it will be impossible to change whatever it is that grounds time experience. This is a problem it is possible to raise whether you believe in substrate dependance or not (thanks to Brian McNiff for raising this point to me).

This might be hard to believe when looking at the scenario. Imagine talking to a slowed down or sped up person again, it doesn’t seem like any part of the conversation function itself is impossible to slow down or speed up. Maybe this is wrong though, or maybe it doesn’t need to be – maybe the conversation is detached from is corresponding consciousness functions, such that you wind up with a passive consciousness practically similar to but technically distinct from denying the modest functionalist claim. That said, it is just hard to picture a part of the mind that is unchangeable like this and also just happens to be crucial to this function, unless you are positing it for the purposes of blocking this thought experiment.

Furthermore the most plausible candidates are specifically limits to compression. Things like Planck units or the speed of light could provide physical limits to how fast functions can be losslessly run. Even in this case however, they wouldn’t provide a parallel problem to slowing the functions down. First of all, if it is possible for a mind to be slower than ours, that proves the concept that subjective time can come apart from objective time, and will have relevance in some possible practical cases (if you run a video of a turtle moving around a toy in fast motion, it appears to be engaging in recognizably normal play behavior. Perhaps turtles are an example we’ll want to examine of animals with slower time perception 6). Recall that denying that experience is slowed down when all functional processes are slowed down is especially absurd, implying that someone can have an experience as of talking with you before they actually talk to you. Second of all though, even if there is a lower limit for compression and so upper limit for speed, what are the odds we are exactly at it? Why assume that some possible creatures (recall the turtle example) can experience time more slowly than us, but that we happen to be the fastest possible minds?

This all might sound hopelessly academic, but insofar as the concept is applicable, this at least means that we need to worry about which beings do or will have differences like this, which could be a difficult question. The case of the fully slowed down human brain is a clean example, and it might even be a relevant one in the future, but in the meantime it looks like most beings who could have this difference in mental perception in the near term, the aforementioned animals or the early beginnings of conscious AIs, will have significantly different brains from ours in less clean ways. If this seems academic, it is because even the practical side of this issue is extremely complicated to work out right now, and requires personal humility in which things count or don’t count as evidence. If it turns out that subjective time is what matters to wellbeing, then some difficult questions about how we treat other minds just got way more difficult (there are some people attempting to at least get started on this question with non-human animals, most notably Rethink Priorities with their “Moral Weights” project 7).

III. Objective Time is Real:

Even if subjective time does seriously complicate ethics however, it might turn out that we have no choice, that it’s objective time that isn’t real. I’m talking here about the third-person accessible variable one finds in physics equations. Here the problem might be more advanced. Namely the common-sense view of objective duration requires the assumption of objective simultaneity. What does the time variable non-circularly describe? Well, a set of slices of space states defined by a variable that allows us to make predictions about one slice based on another using physics equations relating them through a “time” variable. Have a ball at the top of one building and have another ball at the top of a taller building? Time is how you tell where one ball is when the other ball is at a given point in its fall.

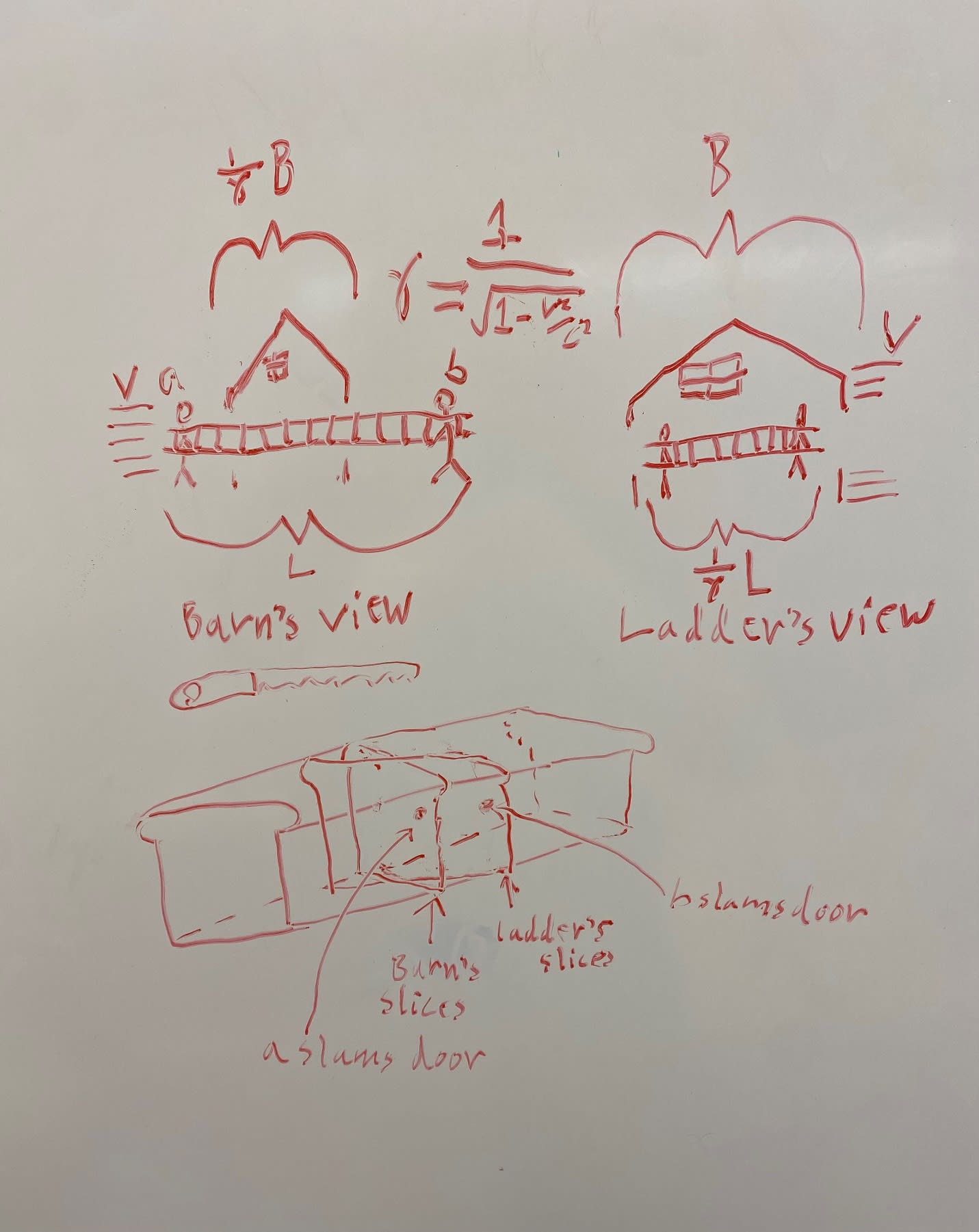

Objective passage of time is the length of these slices all stacked up, and wellbeing over objective time is the amount of wellbeing in this stack. The problem with this idea is rather notorious at this point however – these singular “real” time slices do not objectively exist – at least not in a way that preserves the standard views of physics they appear in. Special relativity instructs us that, if one runs a ladder at great speed through a barn, one can shut the barn doors around it in one inertial reference frame, while it is bigger than the barn in a different one. This is explainable because whether the front of the ladder is inside of the barn at the same time that the back of the ladder is inside of the barn depends on how you slice up the loaf of space and time events (which depends on your inertial reference frame) 8. Lost is our neat stack of correct, real time slices! How much wellbeing is in a stack depends on how fast you are going! I take there to be two significant objections to this line of thought.

For one thing, the time term one reproduces within a relativistic framework might not be the same for every observer, but it is still a difference grounded in different things. All of my arguments about subjective time difference would apply in a world where special relativity is false – and likewise they would still apply if two beings being compared shared the same inertial reference frame or close to it.

But what about the different reference frames? Surely the broader objection isn’t that these two conceptually differ in the same ways, but that objective time doesn’t exist at all. For any given experience, you could decide it lasts any period of time just by imagining moving at a particular velocity with respect to it. This sounds persuasive initially, but breaks when you return to common reference frames – this is how you run into confusions like the twin paradox. The answer, pointed out by Mogensen in his paper, with thanks to Hilary Greaves 9, is “proper time intervals”. There is a single objective duration when following a particular spacetime path, it is only when viewing it from the outside that this is a problem. The proper duration of an experience is the one measured relative to the inertial frame of the experiencer. (what of the extended mind hypothesis 10? Where is this experiencer? Questions I feel are answerable by someone with more tolerance for additional headaches than I).

A final worry is that this is just another version of subjective time. It isn’t arbitrary in the same way as one’s time measured from outside reference frames is, but it’s still some version of “time from one’s own perspective”. True there is only one answer to the question, “what is the proper time interval”, but there’s also only one valid answer to “what is the subjective rate of time experience”. It is easy to understand any subjective information as objective information about one’s own perspective, and surely it’s the “from one’s own perspective” part, not the single correct answer part, that makes something subjective. So why pay attention to proper time intervals at all?

Well, again, these are different senses of time, and they correspond, in turn, to different senses of “one’s own perspective”. “Subjective time” is a slippery concept based on how the mind “measures” time on deliberate observation. It is “one’s own perspective” in the sense that it is one’s own intuitive measurement. Objective time does not rely on one’s own evaluation, it measures the experience in the same way it measures time for anything, including inanimate objects that don’t try to measure times themselves. It is “one’s own perspective” in the sense that it measures the path that the “experiencer” takes, and it is objective in the sense of being a third person dimensional description. A way in which an hour-long headache simply contains more space-slices of headache than a five minute one.

IV. Subjective Time, Simulation, and Delusion:

Still, when comparing the two, it seems as though it is subjective time we most want to care about. This might not intuitively be the case for the practical near-term cases already discussed, such as non-human animals and AI systems. Do we even want to count their wellbeing more based on weird quirks of their minds that don’t make them suffer more in any given moment? The strongest reason to care about doing so is imaginative empathy, or at least principled consistency, when we consider how much more subjective time matters to us than objective time.

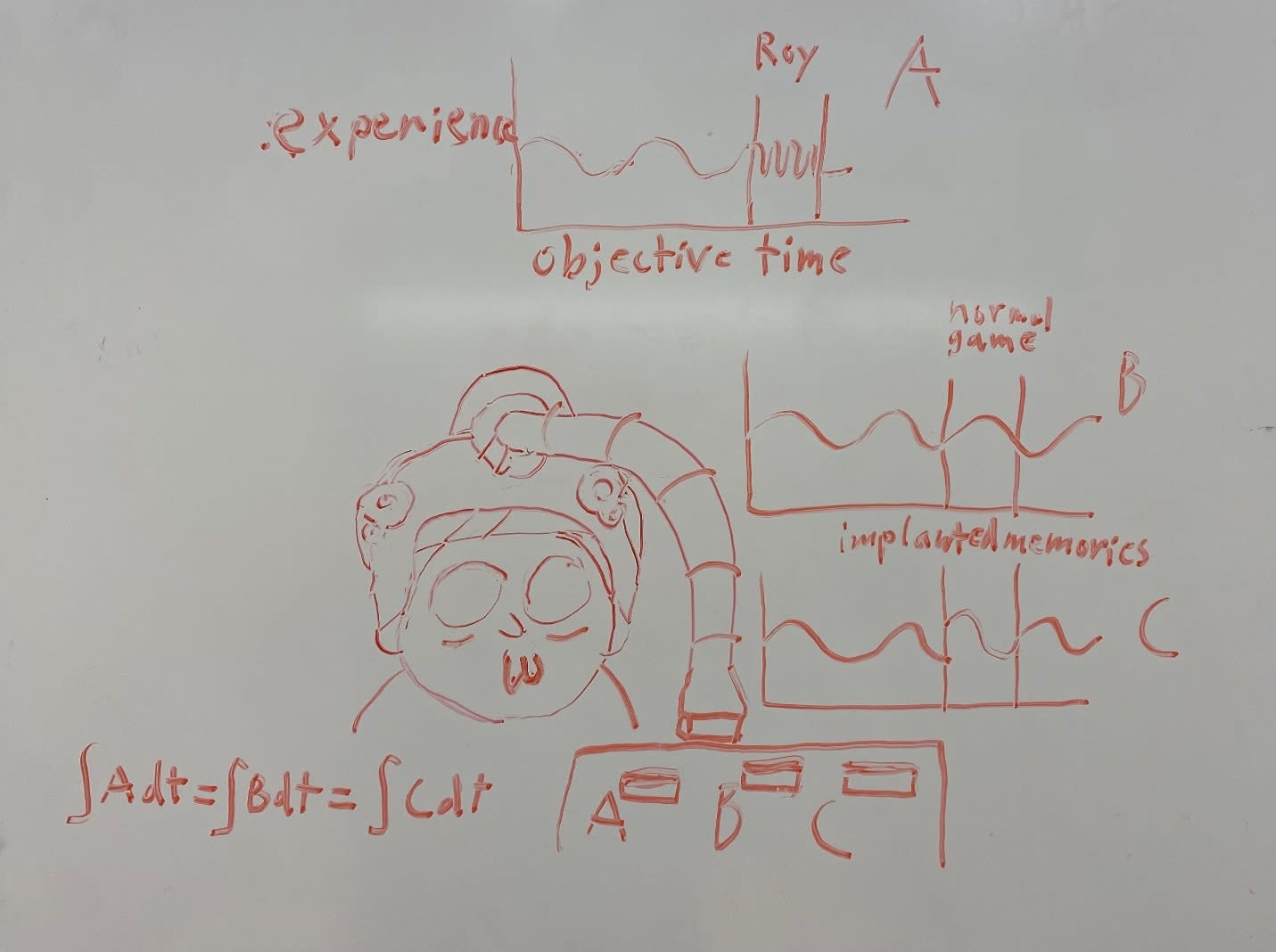

You can test this out by imagining a scenario much like the game Roy from the episode “Mortynight Run” of the sitcom “Rick and Morty” 11. Imagine after you finish reading this paper, you find yourself waking up with someone lifting a VR device off of your head, asking for a turn with the _your name_ simulator. The memories come rushing back, you are in an arcade that includes immersive time compression games. The whole life you just lived up to this point, with every relationship, accomplishment, joy, and pain, was just plugging into one of the arcade games for a few minutes. This is the sort of thing that is treated casually by everyone around you, after all you weren’t really in there for however many years old you are. Sure you felt real suffering and real joy, but whatever the average of them was, only for a few minutes. Who cares? But do you want to simply accept this?

Is there some game you could play for a few minutes in the real world which would give you the same average feeling as the Roy game, which would mean the same thing to you, and specifically to your wellbeing, that what you felt was your whole life has? On some level this scenario feels like it doesn’t quite work. You would have the same initial reaction if you woke up from the game, it turned out your subjective experience was unaltered, but all of your memories were altered instead. You had memories of your whole life, but woke up inside the game a few minutes of its own time ago.

There is also deception in the first Roy case, you don’t know you’re in a game throughout, but imagine that you play the game without being deceived. That you are aware that it is a game the whole time, but everything else in your life goes the same way. If it helps to imagine the significance, you can picture that rather than an entirely personal simulated environment, it is a multi-player game, and you and your loved ones live out loves and suffering and joy and challenges together in the simulated environment for what seems like decades of life before your turn is over with the arcade machine in a few objective minutes. I think it still seems like you couldn’t be convinced, on an intuitive level, that this really just counted as a few minutes to your life.

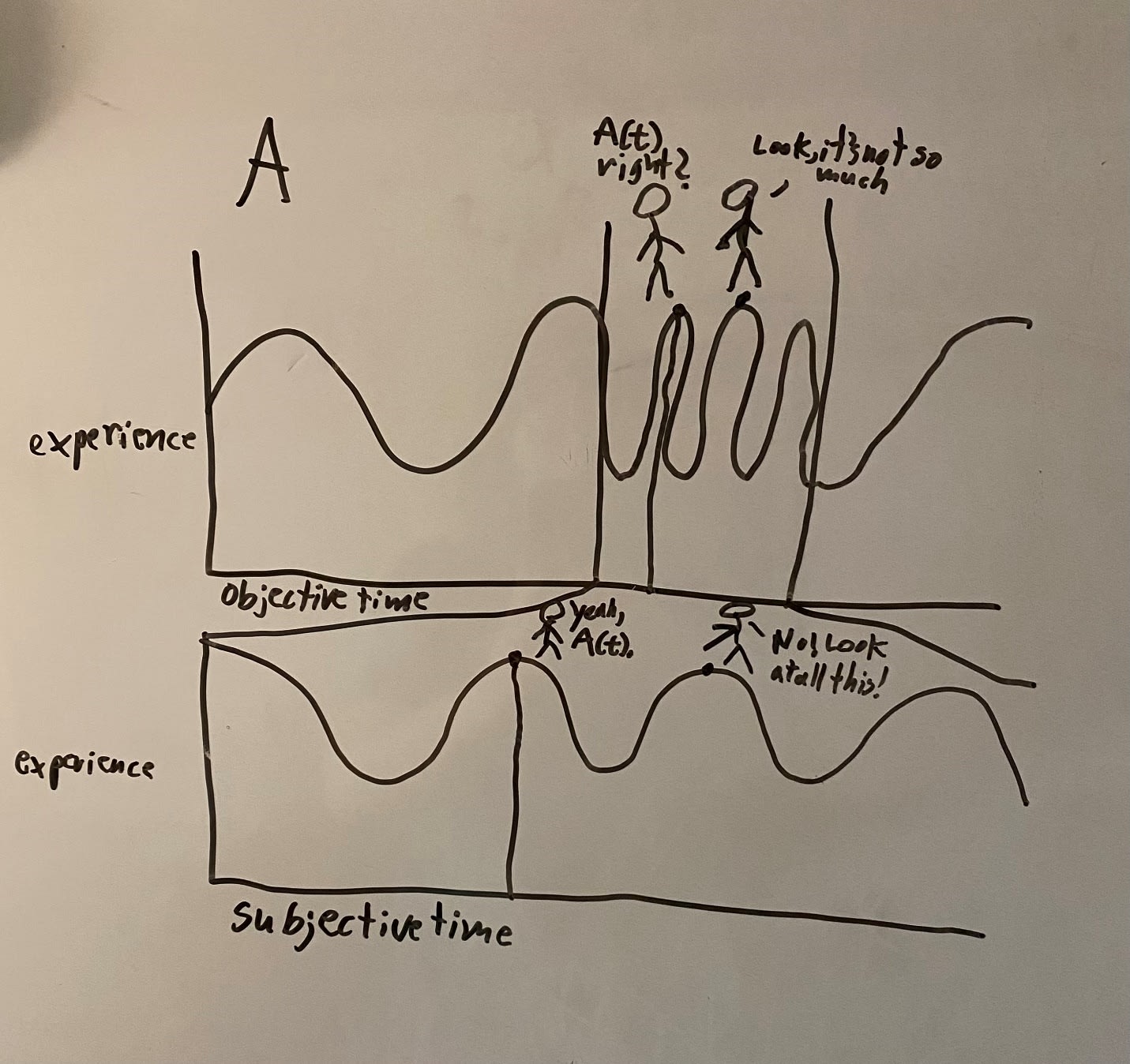

The issue is that spelling this out formally is difficult. Indeed, it is hard to figure out a way of doing it that isn’t still like the implanted memories case in a more abstract way. In the “real” version of subjective time all of the experiences you thought you experienced still exist, they all just last a much shorter period of time, but their evaluated length seems to exist outside of the experience itself. The person measuring via objective time will agree on the existence of every single infinitesimal slice of real experience the subjective experiencer can point to. The difference seems to only come from extending out to adjacent moments, how they relate themselves to the other moments in question – and so at first blush a sort of endorsed delusion about these experiences. This seems to set us up for a situation that is at least abstractly comparable to the implanted memory variation on Roy – we are given the wellbeing contribution of one moment in time, and asked to change our assessment of it based on its evaluation in a later moment or anticipation in a past moment. Compare this to having false memories of a longer past implanted in every moment, so that your evaluation of the past is unreliable even as you accurately evaluate the present moment.

Normally, this does not seem to be good enough. Suppose you are about to undergo surgery, and the doctor is out of anesthetics, but reassures you that, while agonizing, the surgery will still be perfectly safe to perform while you are awake. Instead, they will administer you an immobilizing agent, and an amnesiac, so that after your hellish experience you will entirely forget the surgery. You will wake up with exactly the same memories as if you had been given an anesthetic. Would this sound alright to you? Perhaps the amnesiac would be better than nothing because of trauma avoidance, but I think even if you knew there would be no trauma it wouldn’t comfort you much before surgery to learn that you won’t reflect poorly on it in the future.

More dramatically, we all die some day. At that point we can’t reflect on prior experiences even abstractly, and certainly can’t be traumatized by them anymore. Do we discount or erase all the value and disvalue we got in life when we die? People can even come to reflect on disvaluable experiences in a positive, or even identity-forming light as discussed by for instance Liz Harmon in the context of transformative experiences 12 (thanks again to Brian McNiff, for drawing my attention to this case). It is easy to imagine events that are worse for someone’s life overall, for instance becoming a parent at a very young age, going blind, or getting into a safety school and having very different career options open to you, which leave you in the strange position that you could not have endorsed this event happening to them before it did knowing the alternative paths, but are also unable to regret it after the fact, because of how important it is to what you now value in your life.

But then maybe we can look at prospect if not retrospect, after all I think both agree on the equivalence of objectively different but subjectively equal durations. When I first started writing about this problem while I was an undergrad, I wasn’t able to articulate a solution to it when zooming in specifically and analytically, but felt that it was easy to solve if I took a very big picture on the basic reasons behind my ethics using something like grand prospect 13.

In his 2022 book “What We Owe the Future” 14, William MacAskill asks us to imagine what we would decide to do in our self-interest if we knew we would be reincarnated as every person who would ever live. I don’t know who first suggested this particular thought experiment, I know Andy Weir wrote the short story “the Egg” 15 with a premise like this in 2009, and I came up with it at the time independently in 2018 by reflecting on what I liked and disliked about John Harsanyi’s arguments for utilitarianism 16. I thought something like this provided a better explanation of my ethics, and what made utilitarianism appealing to me as a form of empathetic ethics, than formal axioms did. While I could not answer why subjective time is what matters in terms of standard aggregation-based justifications, I could still obviously recognize that it did based on reflecting on living through all experiences in sequence. If it was this reflection on living each life that ultimately justified my ethics, then it was backwards to demand that it must justify itself in terms of a more formal theory.

The trouble I have since run into is that while axioms only come after the reasons, they are also where you get specific, and the real world is specific. It is therefore easy to deceive yourself into thinking you have a richer answer that entirely gets around a problem, by just strategically losing resolution on it. It is perfectly true that while looking forward onto an experience, I care about subjective time in just the same way that I do by reflecting back onto it, but this doesn’t explain why I do. In thought experiments like this, you can only avoid arbitrariness by assuming the people deciding are prudent or reasonable or something in that vicinity. Given this, you need at least some theory of what prudence or reasonableness are, and so the most this does is translate the question of why subjective time is of value to morality into a question of why it is prudent or reasonable to worry about. Once again, we are back to the same basic questions.

V. What is Subjective Time, Really?

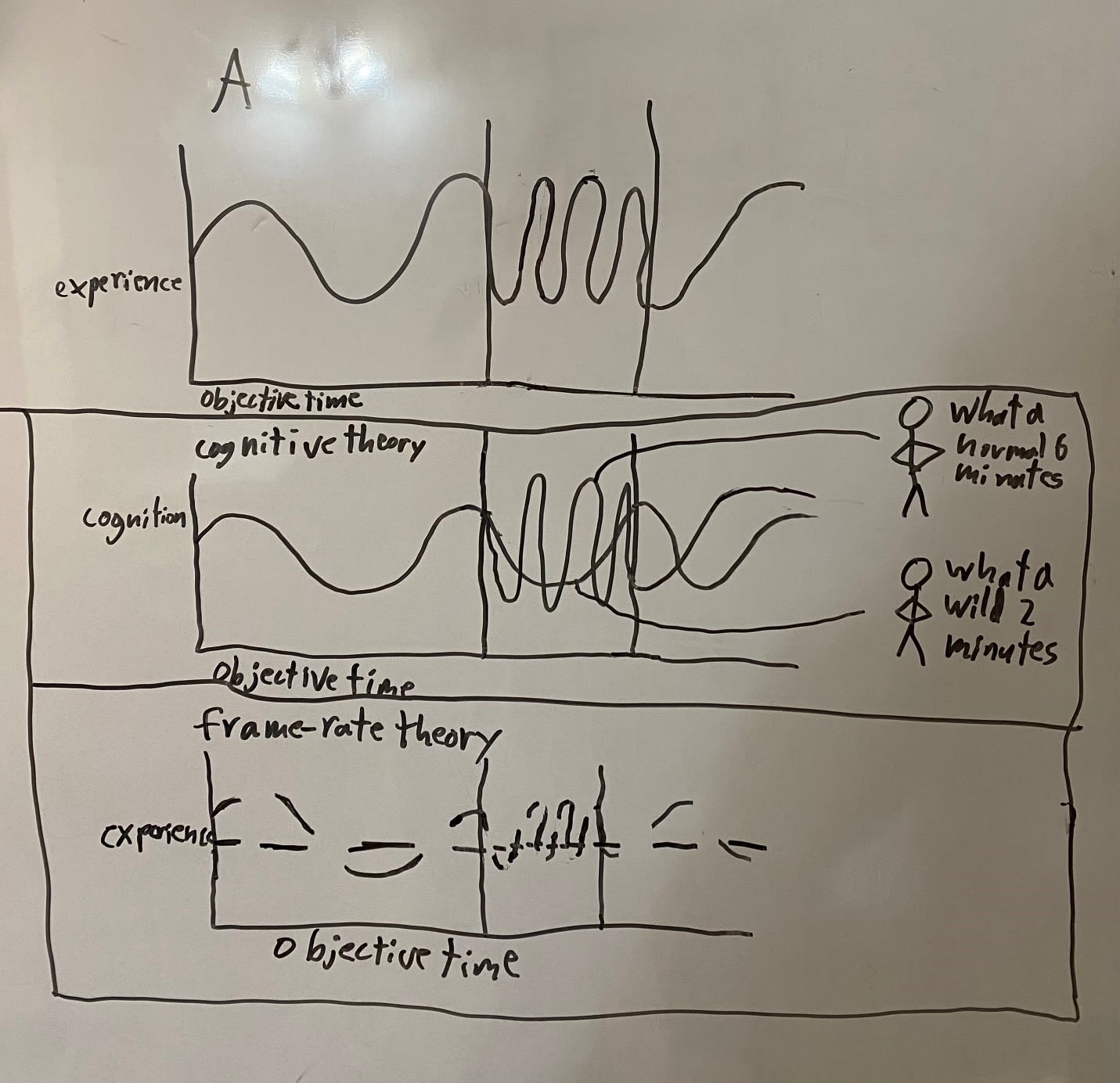

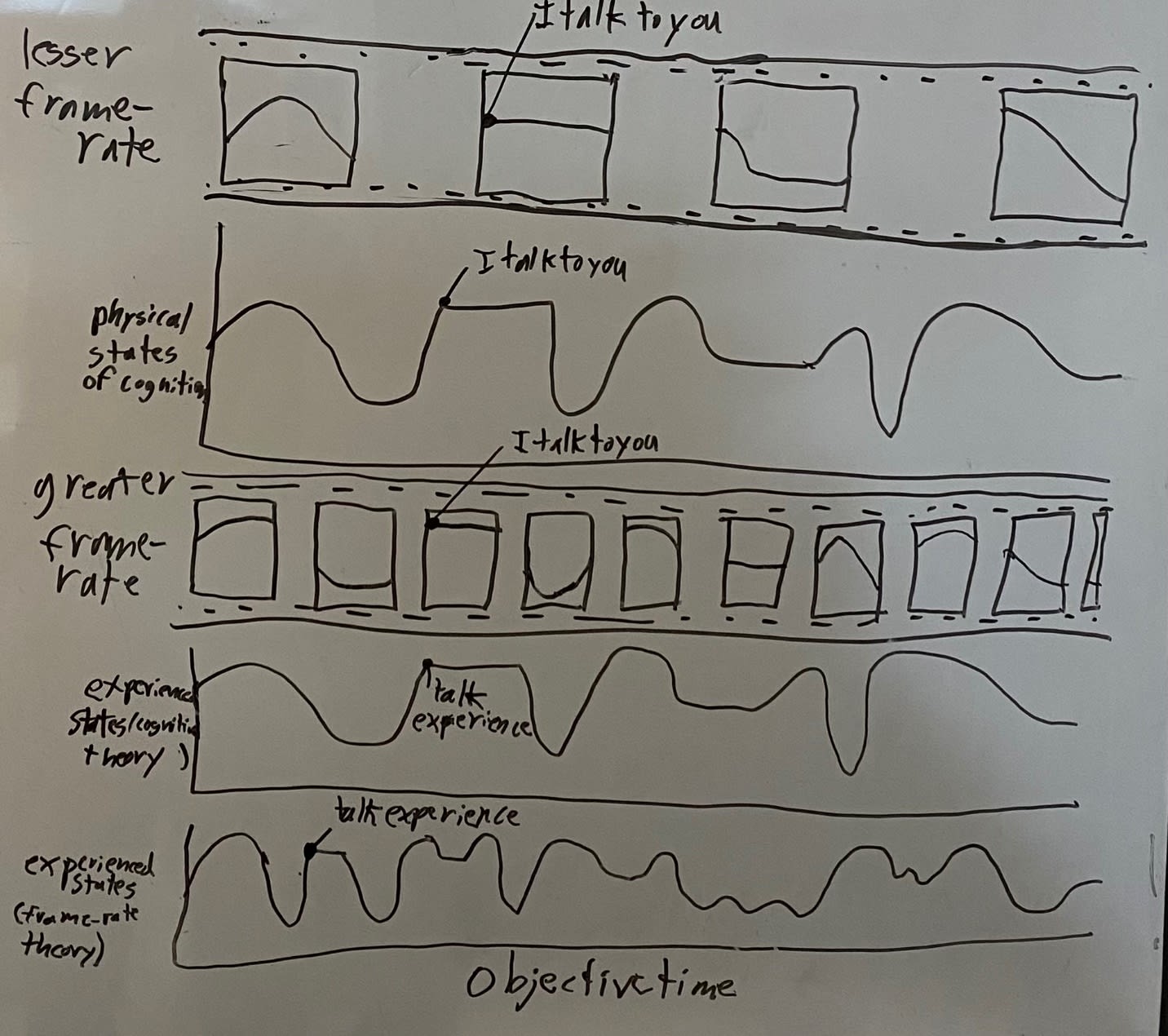

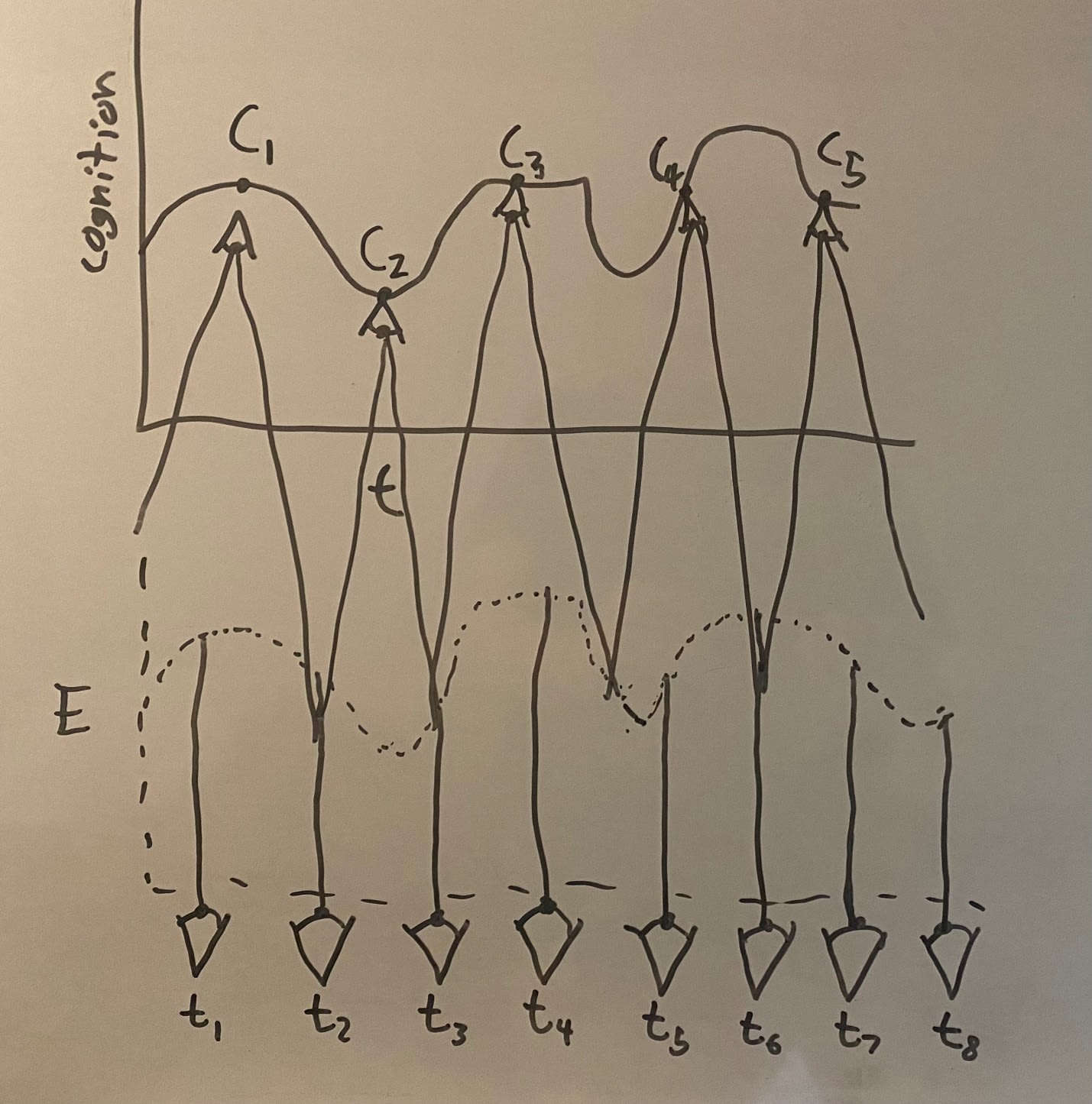

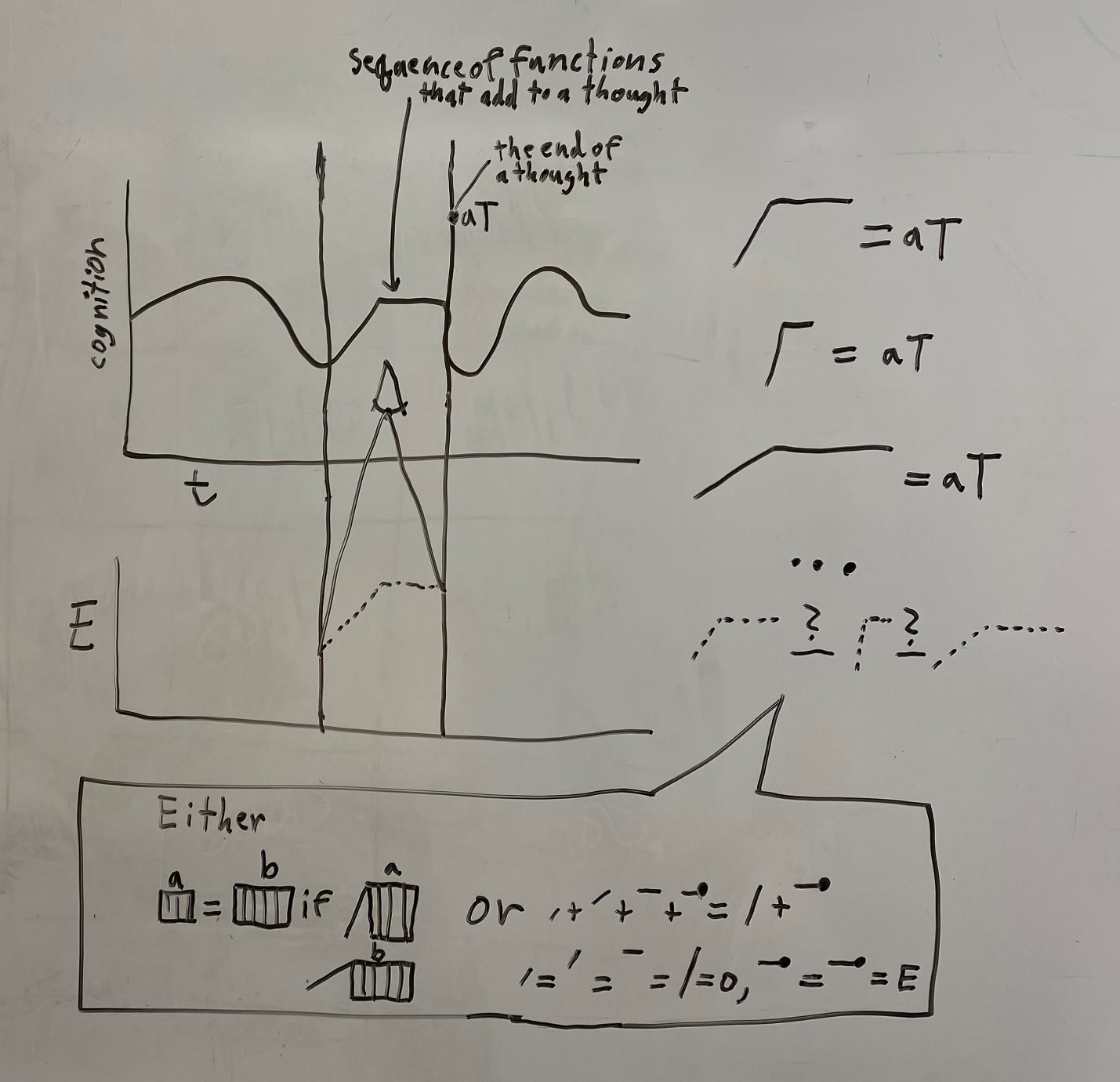

So to review, we are unable to justify our opinions of how much value is at stake in subjective time either by looking at the value one feels from it in each moment separately, or by looking at the value ascribed to it by surrounding moments. Some more big picture theorizing about what precisely subjective time even is will be required to figure out what makes it different from other ways of evaluating experience, or why normal ways of evaluating experience might apply abnormally in this specific case. Andreas Mogensen has been working on exactly this approach 17, by evaluating different theories of what subjective duration even is. In particular, he discusses a cognitive theory wherein subjective experience of time is something like the “speed of thought”, and a frame-rate theory wherein it is how long something like the number of “frames of experience” in a given amount of time.

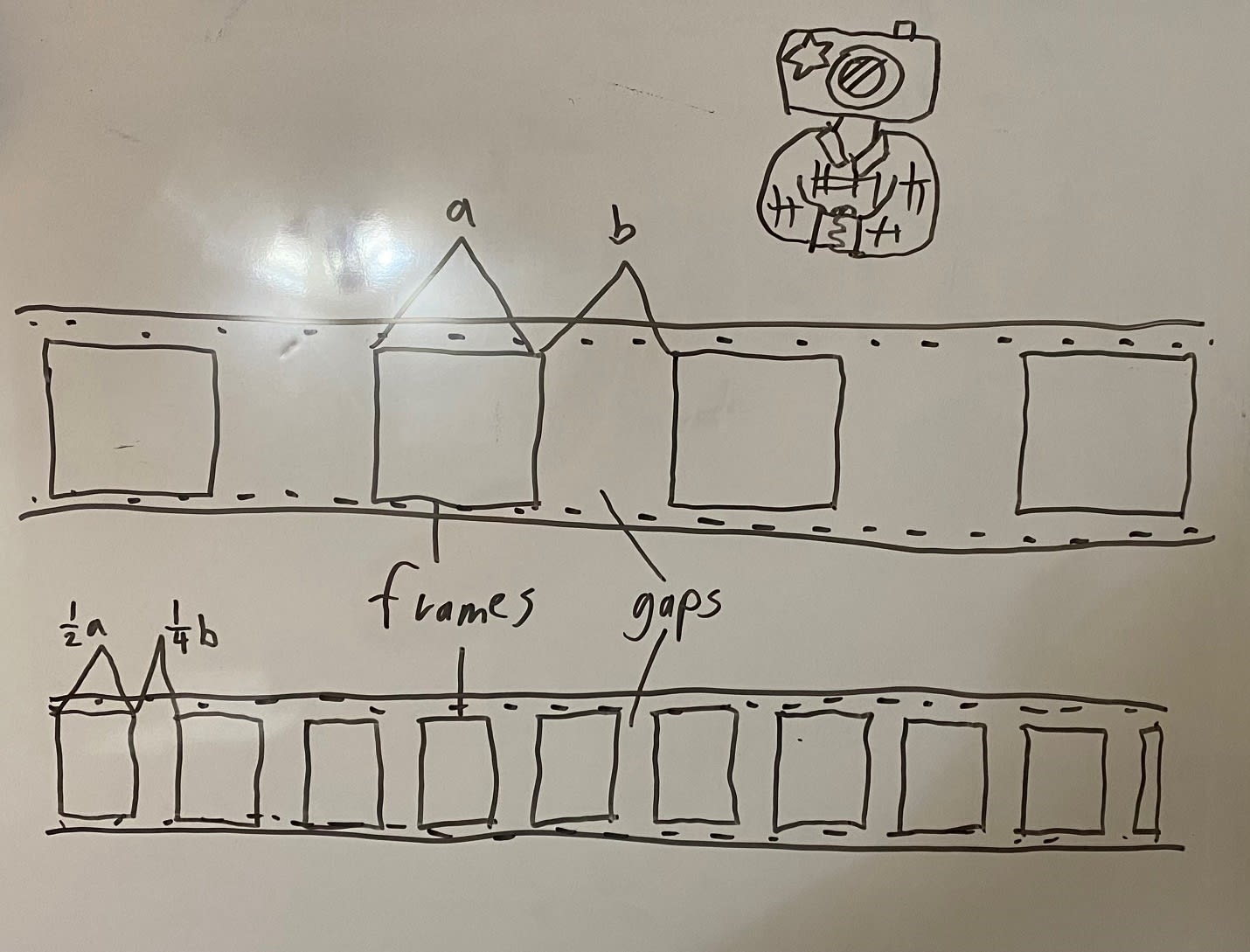

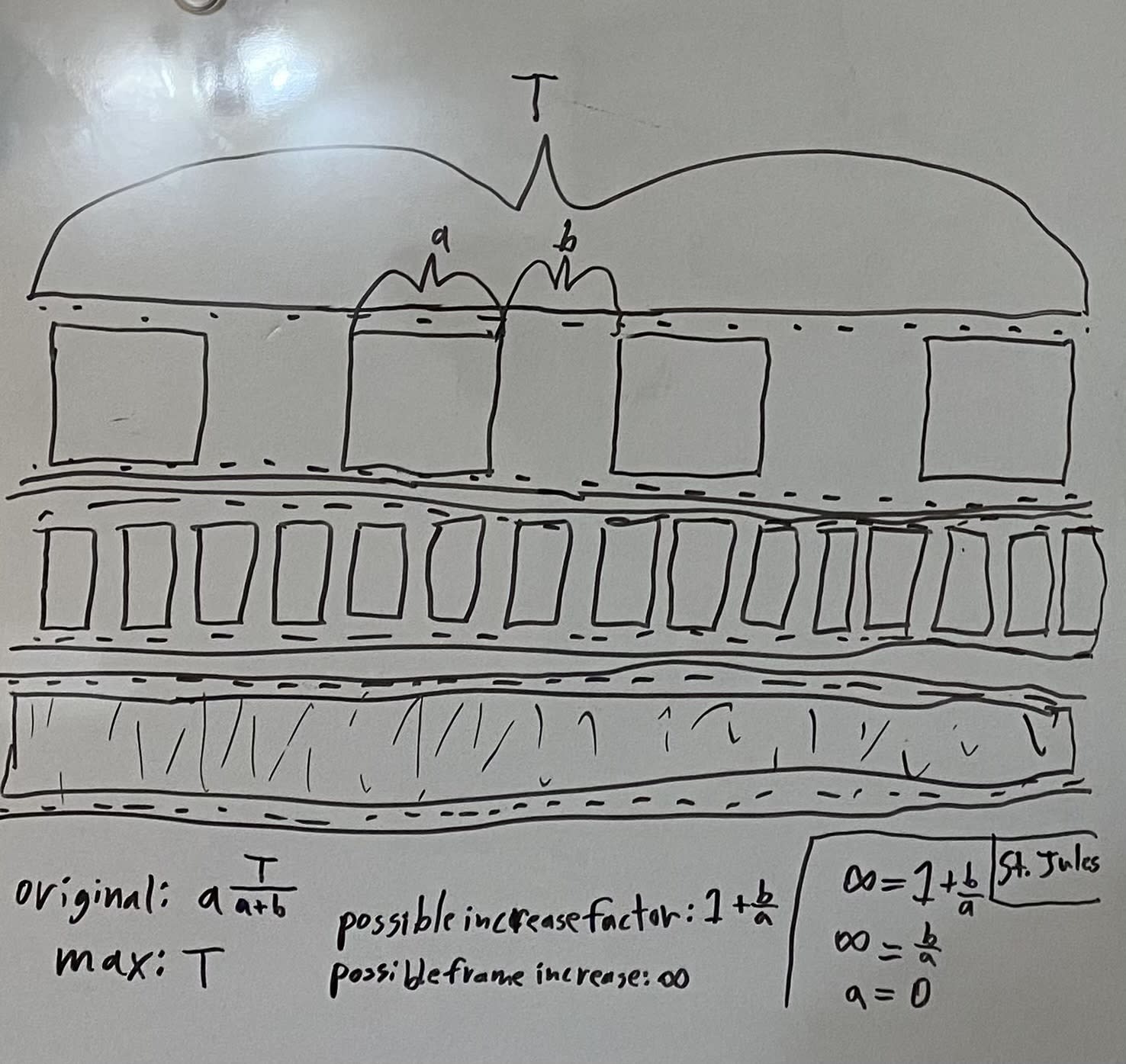

I will start with the latter account, in order to dispense with it. This account is based on the idea that experience is not continuous, but rather there are finite lengths of time that each experience lasts, what Mogensen calls “frames”. Subjective experience of time changes when the length of these frames changes. This means that if you assume there is some gap of time where there is no experience at all between the frames, and increasing frame rate takes up this empty space faster than it reduces the size of the experiencing moments, you can say that faster subjective time increases the amount of overall experience.

There are several problems with this account right off the bat. For one thing, the justification this provides is perfectly compatible with objective time aggregation, as Mogensen notes. This is an argument that there actually is more experience over objective time in subjectively compressed experience. This is of course not terrible on its own, but obviates the need for any additional philosophy.

A more damning objection Mogensen also discusses is that it doesn’t even do a good job satisfying our intuitions that we should care about subjective time rather than objective time. The amount of aggregate experience over these frames approaches an asymptote as subjective time gets arbitrarily faster, since there is a finite amount of possible overall experience – experience over the full time, experience with zero empty space between frames. Say your frames start out as long as the empty spaces between them. No matter how fast your subjective experience gets over one minute of objective time, it will only be valuable, at least based on the empty frames account, as though it was a maximum of two minutes of standard experience. As Michael St. Jules has pointed out 1818), the only way around this issue is if the experiential frames are instantaneous, and so aggregation is a discrete sum of frames. Then you can fit arbitrarily many new frames within a finite span of time without each one’s contribution to the total shrinking. This at least seems unlikely (indeed we are even on shaky ground with the necessary assumption that length of frames decreases more slowly than length of gaps between them).

The very most damning problem with this account though, is that it doesn’t serve as an adequate explanation of what subjective experience of time is. Recall that our modest functionalist argument requires that if all physical processes are slowed down or sped up so that they last a certain span of time, that also must correspond to the experiences of time within them lasting that same span of time. Try laying different cognitive functions onto this span of experience frames and then discretizing them in whatever way is necessary to fit them onto frames. If the frame rate is increased, but the cognitive stream is completed over the same time span, then, again, there is a “jet lag” if the frame rate speeds up the subjective experience anyway. One needs to again either believe it is possible someone can have “an experience as of” talking to you before you get around to talking to them, or to believe that compressing experience detaches you from the cognitive processes at work in the conversation.

Taking this point seriously, increasing frame rate while keeping the cognitive functions the same would merely increase the “resolution” of your experience. In order to marry frame rate to subjective time, first you need to assume that frame rate changes functional cognitive processing as well. This is not too hard to believe, perhaps every frame corresponds to a specific amount of cognition, indeed perhaps the spacing of frames is determined by this in some way, and so more frames per minute corresponds to the same increase in amount of cognition in that minute. This is fascinating from a cognitive science perspective, but helps little with the philosophical questions presented here. In other words, frame rate only corresponds to subjective experience of time if it corresponds in just the same way to the “speed of thought” 19.

This is the first account Mogensen considers, the “cognitive theory”, and it seems to simply be the correct account of what subjective experience of time on the most basic level is if we look back at our initial thought experiment. The rate we experience time at is determined by the rate a certain part of our thoughts is going relative to the stimulus stream in a given moment. That is, a disconnect between the rate these functional processes are altered to, relative to unaltered aspects of the world, like the rate of stimulus in the world outside, and the corresponding amount of time conscious experiencing itself has been happening. Any other theory that differs from the cognitive story must either be ultimately justified by it, or it will wind up denying the modest functionalist claim.

Mogensen doesn’t think that subjective experience of time has intrinsic significance to wellbeing if the cognitive account turns out to be correct. His argument for this is shorter, so I will quote it directly. He says:

“intuitively, a pain is no better or worse merely in virtue of the fact that your thoughts, imaginings, and rememberings seem to move more slowly or quickly in relation to external events while you’re in pain. In and of itself, the relative speed of non-perceptual conscious mental activity is simply irrelevant to pain’s badness.” 20

I will ignore the “non-perceptual conscious mental activity” part of this statement for now, but I take the basic point to be something like this: Imagine we were not asking about subjective experience of time directly, but instead just asking out of context whether the speed of our thoughts during an experience should make us increase the amount we count the pleasures and pains that occur at the same time. It seems unlikely we would think this should matter.

Mogensen elaborates more in a footnote, because the clearest rejoinder is that we would decide that this speed of thought matters once we learn that it is what subjective time is. If this sounds like no additional reason, it could at least be taken as a defense against dismissal. We could compare it to how we would learn that we care about c-fibers firing if we learned that this is ultimately what pain is couched in for instance. Mogensen has a couple defenses here, but perhaps the most decisive one for my purposes is that while we are fundamentally acquainted with pain and what matters about it from the inside, we are precisely trying to explain where the mattering comes in with subjective time, because we can’t find any specific experience where we have the same sort of direct acquaintance with it.

I think the point here is subtle, but ultimately effective. What is mysterious about subjective time experience isn’t just what, precisely, it turns out to be, but where some sort of value can be found in it, and whether this value turns out to be satisfyingly different from mere delusions about past experiences. In fact, considering Mogensen’s points, I think what we are left to round this argument down to is “We care about subjective experience of time. If we learned that subjective experience of time is the speed of thought, then we have learned that we care about the speed of thought. There is no principle behind this, but unlike with implanted memories, learning that it is speed of thought we cared about is not enough to dissuade us from this caring, however arbitrary it is.”

I am drawn to this position myself. It is very difficult to find a principle that satisfyingly explains why I have such an unassailable intuition about subjective time, but while it sounds intuitively fine to deny it in some present and near future cases, I cannot bite the bullet when my own wellbeing is in question, when I picture, for instance, living out the “Roy” game. As with many thought experiments concerning wellbeing, I feel this especially sharply in the case of suffering – I simply cannot tradeoff one second of agony, for a half second of the same agony with my time perception compressed into a million subjective years. In cases like this, I am less drawn to a sort of forced “reflective equilibrium” exercise, and more to admitting that I am not, nor particularly want to be in some cases, a strict adherent to normative principle, even if this erodes some of my self-regard in the process.

That said, I think Mogensen’s dismissal is too quick, and that there is one way of interpreting the cognitive account that is genuinely fairly persuasive. I will lay out this case tentatively, in order to advance a hopefully promising alternative direction for this problem.

VI. It’s Not the Speed of Just any Thought:

The first thing to question is how polluted our intuitions about the relevance of speed of thought are. Mogensen says, reasonably, that when told we will think faster during an experience, we don’t think this should matter to how good or bad the experience is. But there could be strong biases at work here. Famously you can get people to put a higher probability on Ronald Reagan offering federal aid to unwed mothers and cutting federal support for local governments, than they would give if they were simply asked for the probability that Reagan would provide federal aid for unwed mothers in general 21. This of course is backwards, since the former is a subset of the latter, but the extra details aren’t intuitively received as zooming in on part of the set so much as justifying a strange claim. I think something similar is likely true for our intuitions about changing the speed of our thought. If we imagine thinking faster, most thoughts we can picture happening faster would just feel like the rather mundane experience of our mind racing. As a result, I think we picture a sort of average or representative thought racing when we ask about changing how fast we are thinking, but we do not picture “the set of all thoughts” racing, which includes “the most intimate and effortless part of our thoughts”.

It is hard to identify what such thoughts are, but an easy way to draw the line is that, if you go through all of your thoughts and alter their speed one by one, you have found it once your internal experience no longer looks like racing thoughts, but it suddenly starts to look like the world around you moving in slow motion instead. A very natural simplified description of what seems to be happening to you is that, in the first case the thoughts you are having are changing in speed, and when the crucial alteration is made and the slow motion starts it is the thoughts that are you which are changed 22. This is a large part of my gripe with Mogensen’s “non-perceptual conscious mental activity” line. Whatever part of your thoughts needs to be altered must in some sense be the “perceiving” part, it just isn’t the raw stream of feeling measured out moment by moment. It is the functional aspect of this that is altered.

I think this folk psychological understanding of the difference between relevant cognition and irrelevant cognition (one that is the thoughts being experienced and one that is the thoughts that are the experiencer) lead to a framework for viewing subjective time and wellbeing that will lend itself pretty naturally to a response to Mogensen’s challenge. Subjective time is the rate at which a subject of wellbeing unfolds relative to the stream of instances of wellbeing – or looked at the other way, the amount of subject any given amount of wellbeing is happening to.

VII. Container of Wellbeing, Versus Subject of Wellbeing:

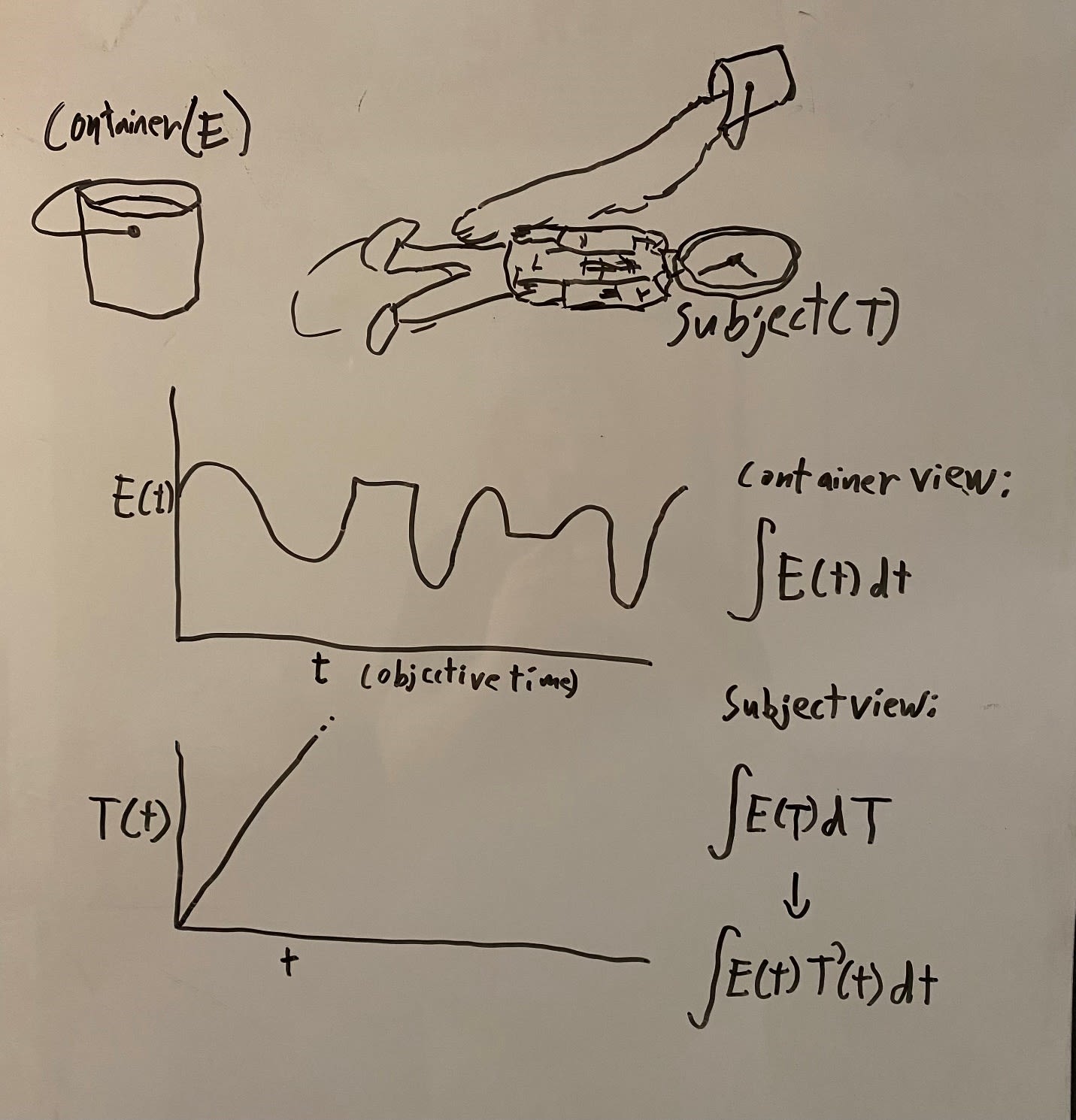

Any theory of wellbeing seems to have both an idea of which beings matter, and an idea of what matters to them. There are two rough categories of theories which vary in how they view each of these components, and it is plausible that they will interpret subjective time differently. One category is the “container view”. Roughly speaking, the thing we take to matter, the “wellbeing”, is the primary interest of the theory. “Subjects” emerge from there as the “containers”, convenient units this amount of value is meted out in, like measuring the water in a bucket. Something like this view is at least alluded to in a couple of related discussions.

Derek Parfit talks about how it is a natural way of understanding totalist population axiologies 23, and why they might be unusually likely to be tied to utilitarianism. Utilitarianism, after all, is interested in maximizing a certain value in the world, and if you make reference to subjects only after the fact, as containers, then one doesn’t even need to reference concerns that totalism cares about “mere possible people”. An even more negative treatment of utilitarianism that appeals to a view like this can be found in Gerald Cohen’s writing on conservatism 24. On his view we have a reason to preserve subjects of value beyond the value they instantiate itself (as an extreme example in line with the population axiology discussion, most people don’t feel neutral about killing someone and simultaneously birthing an equally well-off baby). The mistake of utilitarianism is that it passes right over the subjects and to the value itself. In the process it fails to ask “what is the appropriate treatment of subjects of morality?”

This implies a different view, what I will call the “subject view”. On this view, morality doesn’t primarily concern itself with “what matters”, but rather “who matters”. What matters only comes later, as a theory of how one appropriately responds to the value inherent to subjects. Wellbeing is good specifically because, insofar, and in the way that it is good for someone.

Despite this strong association between utilitarianism and the container view in much of this literature, it is not even clear that utilitarianism needs to be defined in terms of the container view. You can say that the appropriate way to treat subjects is determined by aggregate wellbeing within a life, and the most sensible way to adjudicate conflicts of interest between subjects is also aggregative. John Harsanyi’s classic ex-ante argument for utilitarianism seems easiest to understand on these terms for instance 25, and my own preferred modification 26, based on reincarnation, feels like it puts “empathy with beings that matter” first, and then theorizes that the result of this empathetic view for a prudent and fair agent will look like utilitarianism.

The difference between subject views and container views is not one of logical necessity – you can value any apparently impersonal value as a good for someone, and you can value any apparently personal value impersonally, as something that is good fundamentally for the universe itself. There is no incoherence. The purpose of bringing this difference up is instead justificatory – you cannot explain why any theory which supports totalism must be a container theory, but you can explain why your theory of value would imply totalism under a container view, but deny it under a subject view.

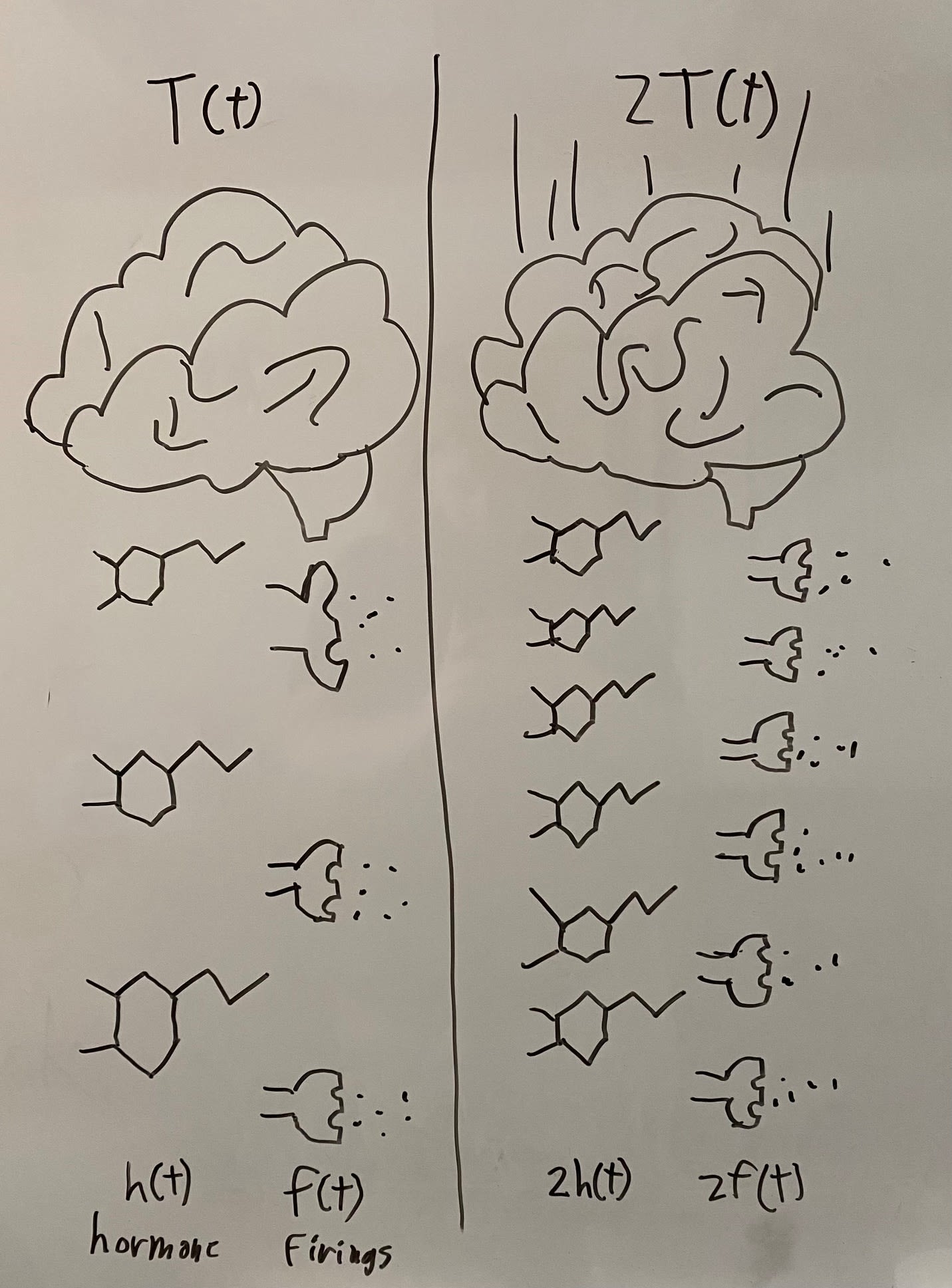

I think subjective time could be an example of such a case for me. The container view doesn’t need to make reference to some value happening to a subject, it will be content with the standard story of objective time – a one hour headache matters more than a two minute one if this means there is more headache in the universe of the one hour headache. The subject view however will have to start by asking who the “subject” is, and then ask a relational question about it: “what would be a good or bad thing to happen to them?” I think it’s a reasonable possibility that the container theory will ultimately be interested in objective time (though I think some of my later explorations in this paper challenge even this), but subject theories ask how much wellbeing is happening to a subject, not to the universe, so it seems like they will ultimately measure in terms of wellbeing over “subject units”. Therefore you no longer need to argue that the wellbeing value itself is altered by subjective time, you can instead just notice that the subject is altered.

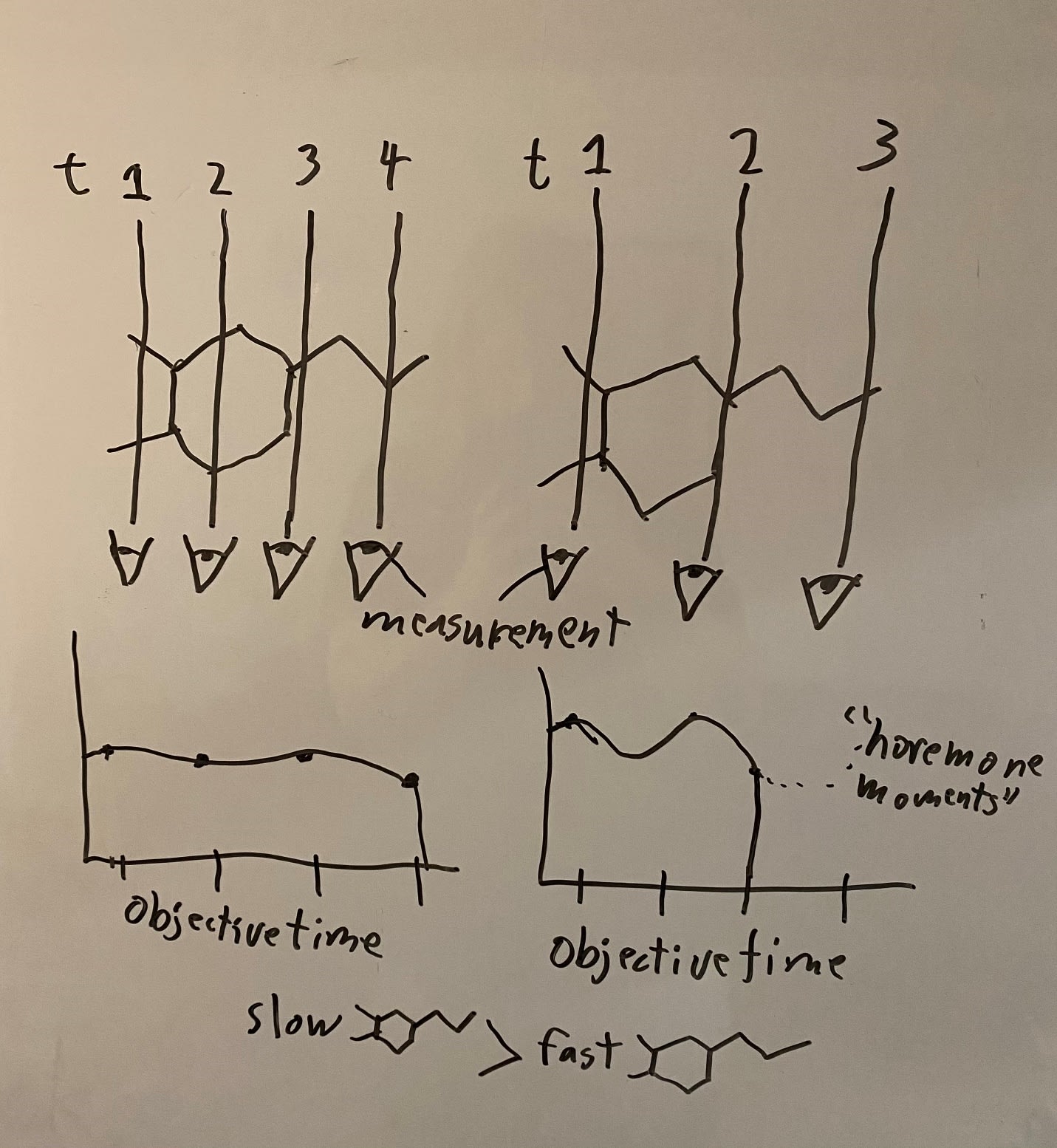

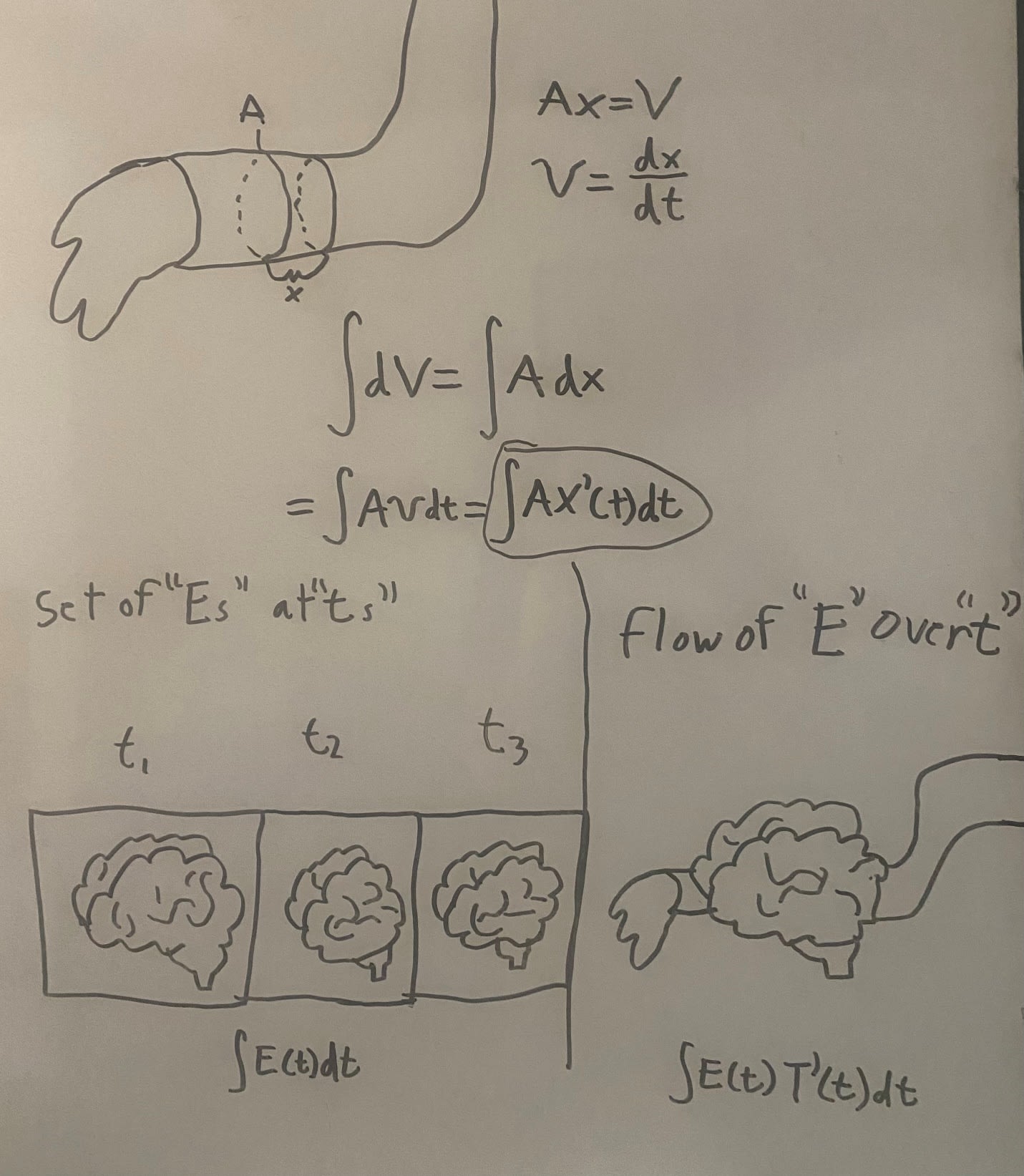

Formalized to be perfectly clear, if you make a simple model of wellbeing aggregation, moment by moment, it will look like ∫E(t)dt where t is objective time, and E(t) is the positive moral value of things like experience over time. The subject model doesn’t aggregate with respect to time at all, but rather with respect to subjects, so you need to replace t with T, where T is the increment of subject rather than time. In order to model this with the cognitive theory in which both streams are compared at different times, you will instead get the parametric integral ∫E(t)T’(t)dt. If the increment of subject is the cognitive stream referred to in the cognitive theory, then this model turns into aggregation with respect to subjective time.

I am not certain that we should choose the subject view at all, in particular there are two major problems that subject views run into but container views avoid. For one thing, the moral circle problem. If you are able to say “this group counts” and “this group does not count”, one obviously runs the risk of dressing prejudice as philosophy. I recently wrote a satirical story about this, in which a series of superintelligent minds set out to justify not counting humans in our moral circle, largely through using more consistent and sharp versions of the divides humans often appeal to in excluding non-humans 27.

On the other hand a common refrain in activism against such prejudiced exclusion is just noticing more sharply that what is good or bad for those we include in our moral circle can also be found in the excluded group. “If you prick us, do we not bleed?” 28 The container view formalizes this in the most direct possible way – we are looking for the thing that is good or bad itself, not first judging different beings “moral subjects” and only then checking for their wellbeing. If you buy into the association between the container view and utilitarian thought, one can even relate this to the unusually progressive record of many utilitarians on social issues, as lovingly documented in Bart Schultz’ “The Happiness Philosophers” 29.

Subject views don’t seem to produce solutions to the moral circle issue that are as elegant on a principled level, or at least trickier philosophy needs to be done to reproduce similar results. The other major worry might run deeper, which is the possibility that experiences don’t come in “subjects” at all. Personal identity might not be (I think is not) a strong further fact in the world, and one can break it with fairly damning edge-case and epistemic arguments 30. This might be a more fundamental issue than the first, but I think it is more answerable. I will leave answering these objections for other work however.

The things that count in the subject view’s favor are perhaps more obvious if subtler to communicate. Much of what people are trying to do ethics for is subjects. Insofar as many categories of value like preference satisfaction, relationships, and yes, pleasures and pains, seem important, it seems basic to the reason for this that they are all things that have a “mattering to” property. They seem conceptually incomplete without their subjects. Once again I think of my earlier infatuation with the reincarnation thought experiment, and the idea of ethics as an idealized empathy. There might be things of moral value that don’t have a “mattering to” property, like beauty or knowledge or something, but it doesn’t seem like we care about these for the same sorts of reasons, and it feels out of the whole spirit of caring about some things to care in the same ways. I am here only defending the inclusion of subjective time in subject views of wellbeing.

The very most basic question my argument raises on this assumption is, “should we think of an ‘increment of subject’ as the same thing as the increment of the cognitive stream referenced in the cognitive theory of subjective time”. There is a trivial confusion that is possible here – the cognitive stream is the part of the mind that the stimulus stream is “happening to”, but does that mean that it is the part of the mind that the experiences are normatively “happening to”? The former is a functional sense of “happening to”, but the latter is more of an ownership sense, who do these experiences count towards. I think simply confusing these two senses makes for an invalid argument, but as I previously discussed, part of the reason to care about certain types of values, like happiness, preference-satisfaction, and relationships, is the functional sense of “mattering to” that they naturally have.

VIII. Are We Our Thoughts, or Our Feelings?

Still, when this suggestion was posed to him, the possibility of misidentifying the subject was the biggest concern Mogensen raised 31, and his alternative is quite credible. I said that the part of the thoughts that are slowed or sped up to change time perception seems to be in some sense the thoughts that “are you”. The logic of the subject-relative standard itself involves identifying the relevant thought stream as the relevant “subject stream” if I want to suggest it. It seems deeply implied by my suggestion that you must identify with the stream of thoughts to aggregate with respect to subjective time.

Mogensen points out that, if we are asked to choose whether we are our “thoughts” or our “feelings” though, it isn’t obvious we should identify more with our thoughts. Indeed, there are some reasons to prefer identification with our feelings. Feelings are where so much of what we care about seems to live – pleasures, pains, our interface with the outside world, our immediate reactions to things like beauty or horrors, our love for others.

Indeed, while it seems at least possible to picture our feelings mattering if they are all that we have, it seems almost impossible to picture us mattering in the same way with only thoughts. A functional cognitive machine with no stream of consciousness inside seems hollow. Maybe it is of value in some way, for instance it might have knowledge or beauty, but crucially the functionally subject-relative categories we can imagine like happiness, relationships, and preferences, no longer seem like they matter or for some of them even exist anymore. It is true that we need a functional sense of “happening to” in order to account for why we pick out these values in the first place, but a natural view of feelings is that they are, indeed perhaps are the only things we know of with this intrinsic property, “happening to themselves”.

None of these points about feelings are entirely uncontroversial, but inconveniently I am sympathetic to all of them (indeed most of them are my words not Mogensen’s). For hedonistic values at least, this leaves us with only one mental stream of interest – the raw feelings. “Speed of thought” plays no immediately obvious role in this, if we are no longer looking to cognition.

One wrinkle for this theory to consider is higher order theories of consciousness. This is the class of theories wherein phenomenal consciousness is fundamentally grounded in higher order states of consciousness – a sort of awareness of awareness (and so feelings only occur as a result of introspection on them). This is a type of theory I was playing with in my head early on in planning this paper, and was raised to me again in discussion by both Jeff Sebo and David Chalmers. I am fundamentally confused about whether and in what ways this theory would help. It would erode the line between the stream of conscious experience (feelings) and the stream of cognition (thoughts), and it seems like it could be relevant if both subjective time and stream of consciousness are grounded in thoughts.

A major worry of mine, however, is that you get the objective stream of consciousness not by looking for a specific way that phenomenal consciousness relates to objective time, so much as by looking for the state of phenomenal consciousness in each moment of objective time, and constructing a set of such moments over time. That is, objective time aggregations don’t draw from some sort of prediction about what metaphysically grounds consciousness that could be disproven, so much as an approach to measurement.

And where is the subjective time in the higher order thoughts? Since the thoughts are about the experiences, it’s easy enough to point to subjective judgements of an experience’s duration, and say that they ground the duration of these experiences. Again though, no one is disputing that there is some sense in which thoughts “feel” shorter or longer, just whether, when we look at an extended set of moment by moment experiences, the beliefs encoded in these feelings are disproven, or if they are commenting on a different aspect of the experiences than the objective time is, and need to face the same scrutiny as to whether and why they matter that other theories about subjective time do. Arguing this could be another promising direction for defending subjective time aggregation.

An alternate way to look at these higher order mental states is as extended thoughts rather than instantaneous perceptions. If a thought grounds an experience, then perhaps we should assume that the same thought, run at any speed, grounds the same experience. This is where timing gets confusing for higher order theories. It seems as though, when the full experiences produced by full thoughts are compared to the sets of momentary experiences making them up, this suggests that the whole determines how much the part contributes to the whole.

If instead we view any given experience as more of a single event, uniquely constituted by the same set of mental functions extended in time that produce the “thought”, we can make a promising if dubious model – mapping phenomenal states in time in this way looks a bit like Michael St. Jules’ infinitesimal frame case, where all experiences are point values, and double the frames always corresponds to double the discrete sum of experiences. Overall, I am too confused by where one could go or where one is limited with higher order theories of consciousness, to do much except make the unoriginal observation that they could interact interestingly with the subjective time discussion.

More boldly though, the example of higher order theories suggests to me that it’s measurement we need to question, not metaphysics. In particular, these graphs of experience over objective time don’t seem responsive to the idea of a “rate of experience” at all. We could assert this is “t”, but why can we talk about thoughts unfolding more quickly or slowly in a given amount of time, but not feelings? Remember, we are not merely looking at time as something feelings happen over, we are looking for the increment of subject, in this case the increment of consciousness itself. As I hope to explore in the following section, I believe the assumptions behind objective time aggregations for consciousness imply the rate of experience is literally unchangeable, but that this is a simplifying stipulation, not a known fact about the nature of experience. And subjective time gives us a more consistent account of how consciousness unfolds over a mind.

IX. Illusionism, Phenomenology, and Measurement:

I think in order to start spotting the possible problems with simply measuring feelings using objective time, we first need to ask what we mean by the “amount of” a feeling. Since we know that we experience events over time, and per the modest functional claim it seems that we must identify these experiences with each moment of their corresponding physical property, we can map experience into objective time by looking for the moment of experience at each objective moment, and adding them up. This sounds like a very grounded, functional way of measuring experience, but it is fascinatingly different from how we measure anything less metaphysically mysterious about the mental event.

If we take a certain amount of hormone being processed by the brain and slow down or speed up the processing, we can find that the same amount of hormone is processed in a different span of time. If we slow or speed up a neuron firing pattern, the same number of neurons will correspondingly be fired in a different span of time. At the extreme Mogensen considers a brain simulation argument that appeals to the exact same functions being executed over different spans of time for altered minds, and dismisses this because, nevertheless, the span of time is different, and so the functions correspondingly produce more or less overall experience 32. In other words, if we use the basic assumptions we need to objectively measure the “experience” part of a mental activity in isolation, then it seems like we aren’t measuring the “amount” of experience like anything else we measure in the world of objective time itself.

I don’t think we need to be surprised if we find a way in which consciousness is exceptional, there’s a reason we have a hard problem of consciousness – because consciousness seems to have unique properties on introspection. However, a parallel problem with this line of reasoning has already come up in one of Mogensen’s own previous points 33 – Unlike properties of consciousness like pains or colors that we seem to have a basic acquaintance with, we are precisely confused about what subjective time even is on the inside. We are already reconstructing the “stream of experience” from an abstracted bird’s eye view - picturing it as though it is spread evenly over a uniform field of third person time is a choice about this reconstruction, not something presented to us naturally in first person experience.

I don’t think you need to make bold metaphysical assumptions in order to measure the amount of mind in a way that is more similar to how we measure the physical brain processes, The very thing we mean by “measuring” over time comes with mereological stipulations – things we treat as the same units of the subject being measured across time. For instance, if we wanted to we could measure any of these physical brain properties over objective time in a similar way to this naive measurement of experience over objective time – there is more hormone processed if it is slowed down and lasts longer, because at any given point in time you can measure how much hormone is in the process of being used at that time, and the same volume of hormone is spread over more such moments. Therefore the cumulative per-moment hormone volume is increased if the same volume is stretched out longer.

Now maybe the right comparison isn’t to the amount of hormone that is being processed at any given point in time, but the increment of additional hormone being processed. This would, indeed, add up to the correct final amount of hormone. However this is something that would instead be increased or decreased in each moment if the mind is slowed or sped up. Either way we can’t give a constant weight to each moment whatever the rate and still wind up with an answer that is what we actually mean by “the amount” of the hormone. Mogensen himself mentions the possibility that subjective time could increase the per-moment intensity of feelings 34, but I think pays insufficient attention to the possibility that – if this is so – it is because we can choose to roll quantitative increases into the moment by moment intensity as an infinitesimal increment for aggregation, rather than as instantaneous levels that we aggregate differently over time. Indeed to continue the physical measurement comparison, measuring flow through a surface area either requires integrating with respect to the infinitesimal increment of volume dV, or simplifying it down to instantaneous units, through what is functionally a parametric integral with respect to distance, x’(t)dt.

Indeed, “amounts” seem like something easier to think about clearly if we think of mental states as literally just neurons firing or literally just hormones. I think this point is only literally relevant for illusionists (even they could measure experience with this even time weighting, but they would be going out of their ways to do so), but I think it illustrates an important point.

The way objective time aggregation asks us to measure “feelings” seems like treating each moment like an independently measured mind and the total as the sum of properties of as many minds as there are moments. Time is not simply a dimension of quantities over time, it typically relates to these by multiplying out momentary “units” of the quantity. For the water flow example, call this the infinitesimal increment of water volume, or separated out from the flow rate, the cross-section of the flow. For hormone we could ask this in molecules, or in volume, for neurons fired, the unit is a “firings”. Whether we are looking at these infinitesimally or instantaneously, we have a more intuitive understanding of the right thing to treat as a “unit” for “matter”, because these units exist infinitesimally in things like “space”. There is no space in consciousness, no mass, charge, or any other obviously quantitative – behavioral properties.

Maybe we should therefore treat these moments as though they lack any unit, and try to return to pure time measurement, but time itself is a third-person, quantitative measurement! We already have to grant that experience spans different third personal positions. Or maybe we don’t deny that time multiplies out some momentary unit, but we call the qualia themselves the momentary units. Level of happiness is like the increment time multiplies out, to give you aggregate happiness. But “level of happiness” seems importantly different from “amount of consciousness”, and I believe the same is true of any qualia described in the first person. It is more like the character of the consciousness, happy versus curious versus sad is less like the increment of volume in a flowing pipe, and more like the pipe flowing with water versus petrolium.

If there is a functional part of the mind that experiences are presented through, then this is more analogous to the normal way we measure physical mental events over objective time for a particular mind. If we treat position in the perceptive cognitive stream in the way position in space acts for the ∫Ax’(t)dt flow measurement, we can exactly reproduce the subjective time integral ∫E(t)T’(t)dt.

This is certainly not an unprecedented way to look at experience, particularly when we look to the continental tradition. In the early 20th century one of Einstein’s biggest philosophical adversaries 35 was Henri Bergson who, as far as I can understand him, viewed “time” as a post-hoc abstraction from processes of motion and change, and that things in motion and change were the primary, prior level of reality 36. It is hard to explain this view directly, but I feel a strong resonance with it because it is the commonsense theory of time I held as a child, and I think many people can remember back to an effortless view of time they once had, before layering abstractions on top of it, that was something like this.

There is a metaphysical boldness to his project is I think unnecessary, and I now disagree with, but subsequently the field of phenomenology began deconstructing the presentation of mental phenomena from a similar basic perspective, with the modification of “bracketing” metaphysical assumptions – working with something closer to my description of measurement as “mereological stipulations”. Husserl, like Bergson, became interested in viewing experience as something in motion, in the sense that it is always experienced as instantaneous accumulation of mental states in change 37. An intentional dance between the past-based assumptions and future-based assumptions cognitive categories are made of. These perspectives have been further drawn together by students of both perspectives on phenomenal consciousness, such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty, with his preferred view of phenomenal time as a sort of product of phenomenal action rather than a passive tape consciousness is rolled onto 38.

I have also heard Taoism invoked several times in conversation, and get the sense that if I were able to better understand it, this would be another tradition which views mind through a related lens. What I hope to add to or take from this for the analytic tradition is that one doesn’t need to glance at this from the corner of your inner eye to view consciousness in terms of subjective time accumulations. Just looking at mind more like an illusionist explains easily why the relevance of time to the accumulation of experience isn’t just projection onto the local proper time. I am not an illusionist, and I don’t think any of these continental thinkers were either, but I think they took the challenge of explaining mind’s participation in the world seriously, and I think it is unsurprising that this should draw us into a closer conversation with those who view the mind as literally identical to a part of this third person world.

X. Conclusion:

Now, I find this response to Mogensen very interesting, and I can almost believe it. But as I have always felt when either on the defensive or offensive with respect to subjective time aggregation, it still doesn’t feel like the complete picture. Rather an elaboration on inadequate prior arguments, such as Jason Schukraft’s arguments for Rethink Priorities 39, and an opening of more specific areas of inadequacy for other people to interrogate. Some inadequacies of the last section’s response alone include:

Could it be that all attempts to incorporate third person functional properties (other than proper time) into consciousness ignore the force of the hard problem of consciousness?

Could it be that the part of the mind that best determines the rate of consciousness is different from the part of the mind that best explains differences in subjective time?

Could it be that reductionism concerning personal identity requires treating a moment of experience the same regardless of its surrounding moments?

Do static mental states lasting different finite lengths of time present a counterexample (something Mogensen discussed in his paper 40)?

I also diverge somewhat from the original framing of my solution by pursuing this particular objection down this particular rabbit hole. I could have defended why we ought to view the stream of cognition as the relevant subject for the subject view. Instead I tried to make a more ambitious claim about the way we measure consciousness to begin with. I like my answer because it presents a view that I think messily identifies the two perspectives as different ways of doing the same thing – either you are measuring the functional and experiential sides of mental events as two separate ideas, or as different dimensions of the same idea. Either way minds must be measured through their connection to one another. However, if it turns out there is good reason to come to different conclusions from these different perspectives, then the most relevant defense would just be that cognition is what we should take the “subject” in subject views to be.

Likewise I only briefly pass over the container view – I expect it to meet an unsympathetic ear immediately from most of my readers, and had to provide my own defenses of why it is even worth treating as a formidable alternative. That said, I base my arguments on granting the subject view, rather than the container view. If the container view turns out to be better, it is, as I briefly discussed, perfectly coherent to care about the exact same things as the subject view, but the principled case becomes weaker – it is coherent to value how much wellbeing over subject unit there is in the universe, to care about E(t)T’(t) directly as your universal value, but the principled reason for caring about this rather than simply wellbeing units across the universe is now deflated, and it appears more ad hoc and unnatural. That said, I am mostly confused about much of what the container view would say here.

I argue in section IX that it is more sensible to think there is a greater “amount of” consciousness in moments where the mind is run faster. Maybe this means that there is simply more wellbeing too? I think this is a place where different theories might come apart. Hedonism is where this is most obviously relevant – perhaps there is a sense in which, not only is more happiness happening to a subject when the mind is sped up, but there is more happiness in the universe in general. I am attracted to this view, but as I previously discussed, it seems as though level of happiness is different from amount of consciousness, does it make sense to talk about “amount of happiness” in a moment as opposed to just “level of happiness”? I am tempted by this because of the cleanliness of distinguishing qualitative and quantitative aspects of the mind, but again this seems like just as good a reason to pay no attention to time in this context. Aggregation of qualities simply seems to require treating “amount” and “level” interchangeably (which is incidentally a big part of my theoretical standoffishness about it).

Other values for wellbeing have even less connection to “amount of consciousness”. How much “preference satisfaction” or “relationship” is in the universe arguably doesn’t need to invoke consciousness directly at all – either as the medium these things occur over, or as the subject they matter to. Discrete versions of most forms of wellbeing value present no problem – say you are counting up achievements, or satisfied preferences, or anything else like this. If you compress or expand your life, then the number of these events remains the same. Maybe this is suggestive that continuous version of any values of this sort should be expanded or compressed as well? Or maybe duration and number of crucial events are both components of many of these values, and so both subjective and objective time matters to them? Truthfully I find the answers to questions like these much less obvious, and much less obviously related to “subjective time”, in the case of container views. If container views turn out to be the better description of the value in wellbeing, then a different, and perhaps more complicated, discussion is required.

Despite these limitations, I think that this paper successfully traces an important perspective on how wellbeing and subjective time relate, one I have been grasping for since my undergraduate years. If it is accurate, we do, in fact, have a reason to pay attention to subjective time when looking for many values in the world. Unfortunately this means we will need to answer some very difficult questions about how our own minds work, and then much different minds from ours. Unfortunately this means that we might need to care a bit more about flies than we otherwise would, and less about turtles than we otherwise would. Fortunately it means that you can take solace that if you wake up in a futuristic arcade after finishing this sentence, your life still mattered just as much.

Acknowledgements:

This paper benefited from the discussion and feedback of Eric B, David Chalmers, Susan Croll, Leo G, Jonathan Knutzen, my genderfluid friend Nick/Heather Kross, Brian McNiff, Andreas Mogensen, Claudia Passos-Ferriera, John Richardson, Jason Schukraft, Jeff Sebo, Michael St Jules, and David Clinton Wills.

References

Bergson, H. (1946). The Creative Mind: An Introduction to Metaphysics. (M. L. Andison, Trans.) New York: Wisdom Library.

Bergson, H. (1965). Duration and Simultaneity: With Reference to Einstein’s Theory. (L. Jacobson, Trans.) Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.

Bostrom, N., & Yudkowsky, E. (2014). The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. In K. Frankish, & W. Ramsey, The Cambridge Handbook of Artificial Intelligence (pp. 316-334). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chalmers, D. (1995). Absent Qualia, Fading Qualia, Dancing Qualia. In T. Metzinger, Conscious Experience. Tuscon: Imprint Academic.

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The Extended Mind. Analysis, 7-19.

Cohen, G. A. (2011). Rescuing Conservatism: A Defense of Existing Value. In R. J. Wallace, Reasons and Recognition: Essays on the Philosophy of T. M. Scanlon (pp. 203-230). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

de Haan, E. H., Corballis, P. M., Hillyard, S. A., Marzi, C. A., Seth, A., Lamme, V. A., . . . Pinto, Y. (2020). Split-Brain: What we Know Now and Why This is Important for Understanding Consciousness. Neuropsychology Review, 224-233.

Fischer, B., Shriver, A., & St. Jules, M. (2022, December 5). Do Brains Contain Many Conscious Subsystems? If so, Should we Act Differently? Retrieved from Effective Altruism Forum: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/vbhoFsyQmrntru6Kw/do-brains-contain-many-conscious-subsystems-if-so-should-we

Frankfurt, H. G. (1988). Indentification and Externality. In H. G. Frankfurt, The Importance of What we Care About (pp. 58-68). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harman, E. (2015). Transformative Experiences and Reliance on Moral Testimony. Res Philosophica, 323-339.

Harsanyi, J. C. (1955). Cardinal Welfare, Individualistic Ethics, and Interpersonal Comparisons of Utility. Journal of Political Economy, 309-321.

Husserl, E. (1990). On the Phenomenology of the Consciousness of Internal Time. (J. B. Brough, Trans.) Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1982). Judgements of and by Representativeness. In D. Kahneman, P. Slovic, & A. Tversky, Judgement Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases (pp. 84-98). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kalish, D. (2019). How Aggregation Can Fail Utilitarianism in the Most Important Ways. RIT Undergraduate Philosophy Conference 2019. Rochester.

Kalish, D. (2024, April 1). [April Fools] Towards a Better Moral Circle. Retrieved from EA Forum: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/rTH2WE5B5gmFDxNoX/april-fools-towards-a-better-moral-circle

MacAskill, W. (2022). What We Owe the Future. New York: Basic Books.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge.

Miller, N. (2024). Evidence Regarding Consciousness in Reptiles. The Emerging Science of Animal Consciousness. New York.

Mogensen, A. (2023, November 14). Welfare and Felt Duration. Global Priorities Institute Working Papers Series.

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Polcino, D. (Director). (2015). Rick and Morty Season 2 Episode 2: “Mortynight Run” [Motion Picture].

Roelofs, L. (2019). Combining Minds: How to Think About Composite Subjectivity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schukraft, J. (2020, August 3). Does Critical Flicker-Fusion Frequncy Track the Subjective Experience of Time? Retrieved from EA Forum: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/s/y5n47MfgrKvTLE3pw/p/DAKivjBpvQhHYGqBH

Schukraft, J. (2020, July 27). The Subjective Experience of Time: Welfare Implications. Retrieved from EA Forum: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/s/y5n47MfgrKvTLE3pw/p/qEsDhFL8mQARFw6Fj

Schultz, B. (2017). The Happiness Philosophers: The Lives and Works of the Great Utilitarians. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shakespeare, W. (n.d.). The Merchant of Venice. Retrieved from Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1515/1515-h/1515-h.htm

St. Jules, M. (2024, January 22). Comment on “Why I’m Skeptical About Using Subjective Time Experience to Assign Moral Weights”. Retrieved from EA Forum: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/dKWCTujoKEpDF8Yb5/why-i-m-skeptical-about-using-subjective-time-experience-to?commentId=hW43cEirwwyixd3vx

Weir, A. (2009, August 15). The Egg. Retrieved from Galactanet: https://galactanet.com/oneoff/theegg_mod.html

Endnotes:

-

(Bostrom & Yudkowsky, 2014) ↩︎

-

(Schukraft, The Subjective Experience of Time: Welfare Implications, 2020) ↩︎

-

(Mogensen, 2023) ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

(Chalmers, 1995) ↩︎

-

(Miller, 2024) ↩︎

-

(Schukraft, Does Critical Flicker-Fusion Frequncy Track the Subjective Experience of Time?, 2020) ↩︎

-

I can’t find the original statement of this famous thought experiment, but thank you to professor Michael Richmond of Rochester Institute of Technology for first exposing me to it. ↩︎

-

(Mogensen, 2023) ↩︎

-

(Clark & Chalmers, 1998) ↩︎

-

(Polcino, 2015) ↩︎

-

(Harman, 2015) ↩︎

-

(Kalish, How Aggregation Can Fail Utilitarianism in the Most Important Ways, 2019) ↩︎

-

(MacAskill, 2022) ↩︎

-

(Weir, 2009) ↩︎

-

(Harsanyi, 1955) ↩︎

-

(Mogensen, 2023) ↩︎

-

(St. Jules, 2024) ↩︎

-